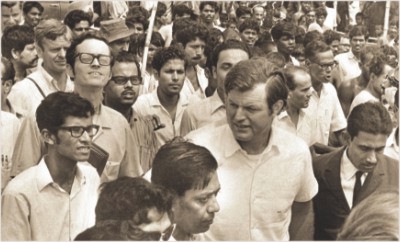

Sen. Edward Kennedy

The Bangladesh genocide of 1971 was basically directed at 3 sets of people: The Awami League was one target, along with leftist students, and then came the main target, the Hindus. they mostly got who they were targeting, especially the Hindu community of Bangladesh.

The Pakistani strategy is evident from the following Sunday Times dispatch on (6/13/71).

“The Government’s policy for East Bengal was spelled out to me in the Eastern Command headquarters at Dacca. It has three elements:

The Bengalis have proved themselves unreliable and must be ruled by West Pakistanis;

The Bengalis will have to be re-educated along proper Islamic lines. The – Islamization of the masses – this is the official jargon – is intended to eliminate secessionist tendencies and provide a strong religious bond with West Pakistan;

When the Hindus have been eliminated by death and fight, their property will be used as a golden carrot to win over the under privi! leged Muslim middle-class. This will provide the base for erecting administrative and political structures in the future.”

The terrible events of 1971 were recorded by Senator Edward Kennedy, and compiled in a report to the U.S Senate entitled Crisis in South Asia. Kennedy described the refugee situation in India:

“A traveler today in eastern India cannot help but see, smell, and feel this misery. It is etched in the faces and lives of refugees in countless ways. It is the malnourished child hanging limply in its mother’s arms – one child out of a half million who, in a matter of hours or days, can easily die from the lack of protein and adequate medical care. It is a young girl, quivering in a refugee camp in Tripura, still in a shock after seeing her mother and father slaughtered by Pakistani troops. It is a 14-year-old boy in Jalpaiguri hospital, whose face is contorted from the pain and anguish that he has experienced since he saw his family shot b! efore his eyes and since he received a bullet wound in his spine which has paralyzed him for life. And it is the expression of hundreds of thousands of refugees living in sewer pipes on the outskirts of Calcutta, while overworked relief officials struggle to provide some food and shelter and hope for a needy and hopeless people.

To drive the roads of West Bengal is to tour a huge refugee camp. For miles along the old Jessore road north of Calcutta toward the border of East Bengal, literally millions of people sit huddled together waithing for food, or line up in endless queues for refugee registration cards, or simply encamp on the roadside under hastily constructed lean-tos. And each day their number continues to grow.

A. THE REFUGEE FLOW

The continuing flow of refugees into India is without parallel in modern history. In less than 200 days-from April 1 to mid-October-more people have found it necessary to flee their homes and lands in East Bengal than the total ! number of refugees generated by the IndoChina war, or the millions displaced by the natural disasters which have struck East Bengal over the past decade. In this short period, 9,544,012 refugees have been officially recorded as having crossed into India, and additional hundreds of thousands have been uprooted and victimized within East Bengal.

Since March 25th a constant stream-sometimes a flood-of refugees has crossed each day into India. The average daily influx of new refugees, according to official reports, has been 48,000-with peak periods in May and June exceeding well over 100,000 new arrivals each day. In May alone, for example, a total of 2,820,922 new refugees were registered by Indian officials.” (5)

So at least 9.5 million refugees had come in from East Bengal. Who were they?

“To avoid communal (religious) clashes, the government, where possible, has tried to keep Hindus and Muslims in seperate camps, the camps being sited in corresponding communal are! as of India. Reflecting the communal representation of the refugees generally, an approximate grouping in many camps, however, is 80 percent Hindu, 15 percent Muslim, and 5 percent Christian and other.” (19)

Kennedy describes the conditions of the camps and the urgent needs of the camp.

“Most of the refugees, however, are poorly educated villagers – the people who make up the bulk of the population in East Bengal. We talked to with dozens of such people on the Boyra-Bongaon Road north of Calcutta, on a day when at least 7,000 new refugees had crossed the border. Nearly all were farmers. Most were Hindus, from districts south of Dacca, on the fringe of the area affected by last fall’s cyclone. Many of these people are still in visible stages of shock, sitting listlessly by the roadside or wandering aimlessly. They told stories of atrocities, of slaughter, of looting and burning, of harrassment and abuse by Pakistani soldiers and their collaborators. Monsoon rains w! ere drenching the area, making it difficult for the refugees to walk and adding to the despair on their faces. To those of us who went out that day to visit refugee areas, the rains meant no more than a change of clothes. But to those refugees it meant still another night without rest, food, or shelter.

It is difficult to erase from our minds the look on the face of a child paralyzed from the waist down, never to walk again; or a child quivering in fear on a mat in a small tent still in shock from seeing his parents, his brothers, and his sisters executed before his eyes; or the anxiety of a 10-year old girl out foraging for something to cover the body of her baby brother who had died of cholera a few moments before our arrival. When I asked one refugee camp director what he would describe as his greatest need, his answer was “a crematorium.” He was in charge of one of the largest refugee camps in the world. A camp which was originally designed to provide low-income and middle-income housing for Indians, but has now become the home for some 170,000 refugees.” (VII)

The lack of crematoriums for the Hindu refugees who were dying lead to more insanity:

“The disposal of dead bodies has posed a serious sanitation problem. In the Hindu community it is customary for the dead to be cremated, but under the circumstances-including a lack of fuel and crematoriums-this has been almost impossible. In some camps local health authorities regularly remove bodies. In others, however, the disposing of bodies is left in the hands of the families involved…bodies are simply left to decompose in a ditch along the road or at the edges of the camps.” (17)

Kennedy describes the terror the Pakistani army inflicted on Bangladesh’s Hindu along with their targeting of the Awami League:

“As the Pakistan army moved out into the countryside to “crush the Awami League,” all evidence-including the simple fact that the bulk of the refugees ! in India are Hindu-suggest this objective was coupled with a policy of terror directed primarily at the minority Hindu population. The following eyewitness field account-filed with the Subcommitte in August and repeated again and again in the Subcommitte files-graphically describes the plight of Hindus in recent months.

***THe next village where we stopped was Mirakati in Barisal district. Our guide, a Hindu, showed us his house, a mound of burned out rubbish from which nothing could be saved. Everything had been burnt to the ground. Every other house in the village was burned out. When we arrived in this village there were no signs of life. However, after a time our guide made signals to a very frightened women who then emerged. She told us that she had seen her husband and child killed and that she is now left alone with one remaining child. Eight days ago the army had came aking her for 100 rupees as payment so that they would leave her alone and unharrassed.

At this ! village there was a brick and cement school that was still standing but everything inside had been burned out. There are supposedly a hundred survivors from this village who are hiding out in the surrounding villages and who are afraid to come out lest they be caught, or shot, or suffer other reprisals.

Village after village we passed was totally in ruins. Sometimes a frame of a house could be seen and at other times every thing was burned to the ground. One of the villages that we passsed was known by the name of Jagadishpur. One of our mission had visited this village previously just after the army’s reign of terror. In one of the tanks of ponds he counted about 100 heads of persons who had been killed and whose bodies were thrown into the tank.

***Of the 36 Hindu villages in the area we visited, they estimated that the maximum number of former inhabitants who have still remained in the area, even though they may be in hiding, would not go beyond 20% to 25%…At peresent ! it is the Muslims who are working the Hindu-owned lands. But everywhere we went on the trip the rice fields were unattended. The only exceptions were these Muslims farming Hindu land. In one village, the original population was about 1,500, of which 100 were killed, 100 remain in hiding in the surrounding area, and the rest have fled.

In some areas, according to eyewitness reports in the late summer, Pakistan troops were painting large yellow “H” signs on Hindu shops, so as to identify the property of the minority which had become a special target. To show they were not Hindus, members of the Muslim majority-although not fully exempt from the army’s terror-were painting sign saying “All Muslim House” on their homes and shops. In turn the small community of Christians were putting crosses on their doors and stitching crosses in red thread on their clothes. Not since Nazi Germany were so many citizens of a country publicly marked with religious labels and symbols.

To do! cument further the mark put on Hindus, additional reports to the Subcommittee have stated that the bank at Barisal was instructed at one point to freeze Hindu deposits. Morever, when units of the Pakistani army later arrived in Barisal, eyewitness accounts say soldiers drove through the streets with loudspeakers announcing a 25 rupee reward for information as to the whereabouts of Hindu residents.

A palpable fear has gripped East Bengal since the devastating night of March 25th. The World Bank Mission, after spending several days traveling throughout East Bengal in early June, was forced to conclude:

“Perhaps most important of all, people fear to venture forth and, as a result, commerce has virtually ceased and economic activity generally is at a very low ebb. Clearly, despite improvements in some areas and taking the Province as a whole, widespread fear among the population has persisted beyond the initial phase of heavy fighting. It appears that this is not just a concommitant of the Army extending its control into the countryside and the villages off the main highways, although at this stage the mere appearance of military units often suffices to engineer fear. However, there is also no question that punitive measures by the military are continuing; even if directed at particular elements (such as known or suspected Awami Leaguers, students, or Hindus), these have the effect of fostering fear among the population at large. At the same time, insurgenct activity is continuing. This is not only disruptive in itself, but also often leads to massive Army retaliation. In short, the general atmosphere reamins very tense and incompatible with the resumption of normal activities in the Province as a whole.”

Report after Report over the summer months echoed the findings of the World Bank Report-as did hundreds of interviews with refugees in India, including new arrivals, by members of the Subcommittee’s field team. The emergence of Be! ngali guerilla units, known as Mukti Bahini (Liberation Forces), have brought an added dimension to the violence and chaos and fear throughout East Bengal. A dispatch from Faridpur district, published in The New York Times on September 23, describes the continued violence as follows:

*** Nira Pada Saha, a jute trader in Faridpur District told of a reprisal against a village near his that had sheltered and fed the guerillas. Just before he fled five days ago, he related, the army struck the village, first shelling it then burning the huts. “Some of the villagers didnt run away fast enoght,” he said.”The soldiers caught them, tied their hands and feet and threw them into the flames.”

There were about 5,000 people in the village, mostly Hindus, Mr. Saha said, and not a hut is left. According to the refugees, the army leaves much of the “dirty work,” to its civilian collaborators-the razakars, or home guards-it has armed and to the supporters of right-wing religio! us political parties such as the Moslem League and Jamaat-i-Islami, which have usually backed the military regime.

The collaborators act as as intelligence agents and enforcers for the army, the refugees say, by pointing out homes and villages and people who have helped the guerrillas. Often, the refugees added, the collaborators make arrests at random and for no reason. “The razakars and the others come into a village and pick just any house,” said Dipak Kumar Biswas, a radio repairman from Barisal District. “Then they arrest whatever able-bodied young man is in that house and hand him over to the army. We don’t know what the army does to them. They never come back.” (47-49)

In his conclusion, Kennedy states:

“Nothing is more clear, or more easily documented, than the systematic campaign of terror-and its genocidal consequences-launched by the Pakistani army on the night of March 25th. Field reports to the U.S government, countless eye-witness journali! stic accounts, reports from international agencies such as the World Bank, and additional information available to the Subcommitte document the continuing reign of terror which grips East Bengal. Hardest hit have been members of the Hindu community who have been robbed of their lands and shops, systematically slaughtered, and, in some places, painted with yellow patches marked “H”. All of this has been officially sanctioned, ordered and implemented under martial law from Islamabad. America’s heavy support of Islamabad is nothing short of complicity in the human and political tragedy of East Bengal.” (66)

As you can see in a couple of the eye-witness dispatches filed, the Pakistani objective of using Hindu land as a carrot for under-class muslims was being achieved.

A couple estimates of the Hindu death toll can be found at

Look at lines 43 and 44 under “Hindus – death toll”: Porter estimates it around 2 million, Roy around 3 million. In between 2 and 3 million should not be surprising given the eye-witness accounts and the simple fact that the majority of the refugees (80%) were Hindu. The following population figures for Hindus in Bangladesh do not look normal from 1961 to 1974.

Bangladesh Hindu Population, July 2000: 13.565 mill (10.5 %)

Bangladesh Hindu Population, 1981: 10.633 mill (12.2%)

Bangladesh Hindu Population, 1974: 9.655 mill (13.5%)

Bangladesh Hindu Population, 1961: 9.411 mill (18.5%)

Bangladesh Hindu Population, 1941: 11.76 mill (28.0%)