One has to hand it to The New York Times. If you can’t be overtly racist and negative on India, the next best thing to do is to get a disgruntled Indian intellectual, someone cut off from his roots, to do the job. No one can then accuse you of racism.

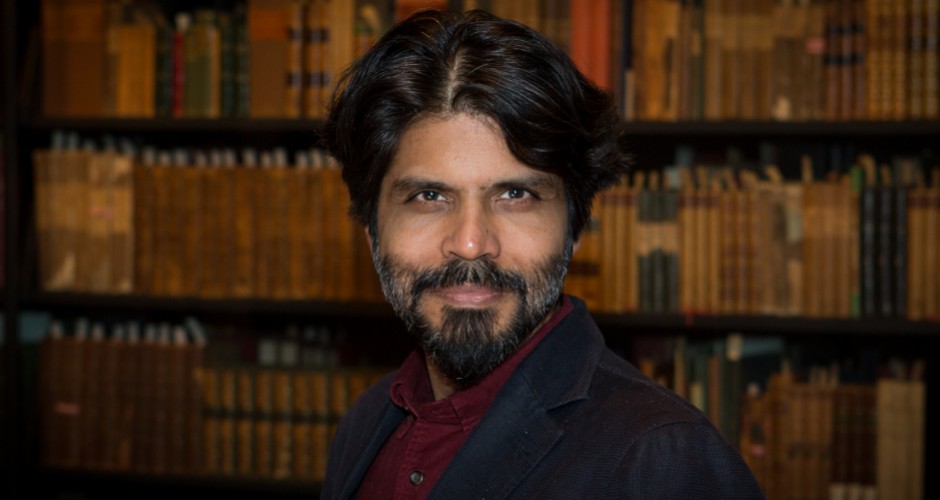

This, in short, is the story of Pankaj Mishra, the much-acclaimed author and general hater-in-chief of anything Indian. In a recent article in the NYT, Mishra, while noting (correctly, in my opinion) the typical Indian envy of the west while simultaneously craving western approval, completely loses it and says the rise of Narendra Modi and the traditional right is something more dangerous than ISIS. He writes: “Largely subterranean until it erupts, this ressentiment of the West among thwarted elites can assume a more treacherous form than the simple hatred and rejectionism of outfits such as Al Qaeda, the Islamic State and the Taliban.”

One is not planning to discuss all of Mishra’s rants here (for that, read here and here), but two points are worth making.

First, the ressentiment is as much from the NYT side and racist elements in the west as from India. Else, why would publications like the NYT, Guardian, Washington Post and The Economist suddenly unleash a torrent of negativism against the new government in Delhi? They can obviously live with the despotic Chinese and Saudis, but not a democratically elected Indian PM? More important, how is it that these publications always use only the Pankaj Mishras, Amartya Sens, Arundhati Roys and Martha Nussbaums to write on India, asks Vamsee Juluri in his book Rearming Hinduism. These are largely people with a jaundiced view of India and Hinduism. Does the NYT think there are no opposing viewpoints worth considering? The newspaper’s editorial board needs to ponder about how fair it would be for an Indian publication to use only the views of Noam Chomsky or (the late) Malcolm X to write about America.

Second, the Mishras and Roys of the world, in a sense, reflect the pathology of self-hate that can come only from a long-internalised criticism of India and Indians that came with British colonialism and religious evangelism. The colonial administration and its proselytisers needed to paint the natives, their customs and practices as wholly evil and savage in order to justify their colonisation of India. This is not to say Mishra is justifying colonial rule, just that he has internalised the colonial attitudes and does not want to let go of it.

In fact, the Hindu-phobic secular elite in the west (and in India) are the other side of the coin which has a rabid Hindutva face. When you internalise western criticism of your society so much, at the extremes you can end up with one of two reactions: self-hate or denial. The Mishras are the self-haters, who see everything in India and Hinduism as negative. The deniers are the rabid Hindutva votaries, who deny that anything was (or is) ever wrong with our society. Everything about our past was great and good.

The truth, as always, lies somewhere in between, and this is what the Mishras of the west are unable to digest. If the politics of the last one year has proved anything, it is not that India is longing for a rabid version of Hindutva, but that, for the first time, Indians in large numbers are breaking out of their old mindsets of caste and class and trying to evolve a new development paradigm that seeks to talk to a better future. It would be fair to say that the rise of Modi has not yet addressed the concerns of the minorities, but in all his formal statements, Modi, post-election, has been talking development, inclusiveness, and citizenship. He has risen to power not because of his Hindutva, but his ability to see the new, aspirational India for what it is.

It is fair – for westerners and truly secular individuals – to retain doubts about whether the Modi of 2014 is the same as the Hindutva icon of 2002, but rational observers should wait before they pass sweeping judgment on the man and his mission even before it has really taken shape.

Moreover, the real issue is not Modi, but a western fear that India, may, after all, start rising on the world stage. Mishra’s views are intended to pander to western fears of their inevitable decline as China, and now India, offer signs of revival.

The west knows it can do damn-all about China’s rise, unified as it is culturally by a 5,000-year civilisational history and protected by mercantilist policies. Britain and the US became world powers primarily with the aid of mercantilist policies. However, what the west cannot stomach is India’s rise. After all, having told us repeatedly that there is no such thing as India, that there was no civilisation here before the Brits landed on our shores, that India is a mere “geographical expression” and that Hinduism was something invented by European Indologists, a new India taking shape is more threatening to western views of themselves than China’s rise. The works of writers empathetic to Hinduism, like Rajiv Malhotra and Koenraad Elst, show how the Hindu mind has been colonised in the past. Many Hindus are beginning to think out of this colonial box, but the Pankaj Mishras want to put them back in.

The intellectual challenge to the western paradigm of belief in holy books, god, and the culture of annihilation will come not from authoritarian China, but from democratic and liberal India, which is rediscovering its Hindu-Buddhist-Jain cultural moorings after being severed from it for so long.

It is this new empowerment from within that the west fears, and which Mishra seems resentful about, having chosen to become part of the western establishment. He fervently wants the west to believe his version of India; ironically, he is seeking exactly the same white man’s approval that he accuses ordinary Indians of. He can neither stand an eastern view of the west (Rajiv Malhotra’s Being Different) or even independent western voices like Patrick French (author of India: A Portrait). Mishra accuses Malhotra of producing “piffle” about “integral unity” and French of being a modern-day Lord Curzon.

French gave it back in spades after Mishra’s dismissive review of his book in an Outlook article: “For a reviewer, it is the cheapest shot in the locker to compare any foreigner you disagree with to a British imperialist….Perhaps it is Pankaj, with his high, sanctimonious tone and his migratory bio (he apparently divides his time between Delhi, Shimla and London) who sounds more like the viceroy Lord Curzon.”

French writes further: “Pankaj has obviously been on a long journey from his self-described origins — in what he calls a “new, very poor and relatively inchoate Asian society” — to his present position at the heart of the British establishment, married to a cousin of the Prime Minister David Cameron. But he seems oddly resentful of the idea of social mobility for other Indians.”

I couldn’t have put it better. Mishra’s is the lament of the India expert who panders to western stereotypes of India. His greatest fears are that his voice will now be drowned in the rise of new, more independent, voices that can talk more authoritatively about a changing India.

Both NYT and Mishra need to wake up and smell the new coffee brewing in India.

by R Jagannathan

First Post