In civilisations and cultures without explicit good and evil there was no need for the Devil, Satan, Lucifer or just simply the ‘Evil One’. The demonology of one god thrust upon humanity by monotheism needed a polar opposite in the form of the Devil. Hence the inherent contradiction in which this supposedly superior belief in one God needs a simultaneous adherence to that of one Devil.

Everything good, pure and righteous comes from this God. By virtue of this, everything evil, noxious and impure comes from the Devil. This demonic force is necessary for the monotheistic deity to have any influence at all, a stick to chastise his earthly subjects who become just mindless automatons created by this God as mere playthings for his divine power, as well as that of his alter-ego who subdues them through temptation.

Asura as Demon

Vedic interpretations saw the universe as caught between dualistic antagonisms of Devas and Asuras. These are often translated as ‘gods’ and ‘demon’s but is more complex than that facile bifurcation. In Hinduism, Jainism and Buddhism there is no monotheistic God or Devil, no eternal damnation. Reincarnation through the law of karma offers hope in the afterlife.

Vedic interpretations saw the universe as caught between dualistic antagonisms of Devas and Asuras. These are often translated as ‘gods’ and ‘demon’s but is more complex than that facile bifurcation. In Hinduism, Jainism and Buddhism there is no monotheistic God or Devil, no eternal damnation. Reincarnation through the law of karma offers hope in the afterlife.

Shiva can sometimes be portrayed as ‘demonic’, and yet in other forms benevolent.In his 1998 book ‘Awaken Bharata’, David Frawley explains the difference between light and dark mysticism.

Devic exists for purpose of union with the higher self, using yogic principles of truthfulness, non-violence, self-control, asceticism and meditation, promoting peace, love and selflessness. It uses sattva guna, the quality of light, purity and goodness.

Asuric mysticism on the other hand exists for domination using the powerful ego, and does not hesitate to employ aggression, violence, anger, and pride. Its emphasis is conquest of the physical world not the inner self. This power-seeking mentality is dominated by rajoguna in its restless urge to assert and expand. Frawley on page 139:

The Asuras are the forces of matter and the underworld. They manipulate people through lower vital urges of power, sex, money and drugs. They can use commercial methods, like advertisement, which is a kind of mind control, or political propaganda to stir up passions and desires. However they can take on a religious front in order to further develop their aims.

But the boundaries are not always clear cut. They often mix and merge according to the circumstances. Devic methods can easily morph into Asuric, especially when the latter use Devic methods of a highly trained mind whose purpose is then turned to aggression. Page 142:

Yet the duality between the Devas and Asuras is not absolute and should not be confused with any simplistic good and evil. The Asuras represent elemental energies and vital passions, the forces of rajas (rajoguna), which have their place in the cosmic order.However, these powers of action must be subordinated to the higher laws of the Devas (the forces of mind and spirit) and sattva guna (peace and clarity) for them to function properly. A Divine or sattvic type of action or rajas must become dominant, absorbing the active force into a higher aspiration, making the Asuras serve the Gods.

Hence the Asuras cannot be destroyed, only subdued. When the gods become weak the Asuras emerge from the underworld to take control and fill the vacuum due to their restless energy. But they have their place in the cosmic order, to keep Devas and humans vigilant. The Asuric Shakti only becomes powerful when the Devic Shakti is weak.

Rahu is a case in point to understanding that the Asura-Deva division goes beyond just mere dualism of good and evil. After the head of Svarbhānu, an Asura, was cut off by god Vishnu, his head and body joined with a snake to form ‘Ketu’, representing the body without a head, and Rahu, representing the head without a body.

Rahu is a case in point to understanding that the Asura-Deva division goes beyond just mere dualism of good and evil. After the head of Svarbhānu, an Asura, was cut off by god Vishnu, his head and body joined with a snake to form ‘Ketu’, representing the body without a head, and Rahu, representing the head without a body.

He is therefore a severed head of an Asura, that swallows the sun causing eclipses.

Rahu is one of the navagrahas (nine planets) in Vedic astrology and is paired with Ketu. The time of day considered to be under the influence of Rahu is called Rahu kala and is considered inauspicious.In Vedic astronomy, Rahu is considered to be a rogue planet.

As well as being the advisor of the demons, the minister of the demons, ever-angry, the tormentor, bitter enemy of the luminaries, lord of illusions, one who frightens the Sun, the one who makes the Moon lustreless, he is also the peacemaker, bestower of prosperity and wealth and ultimate knowledge.

In Indian astrology, Rahu dasha can either be the best time of any person’s life or plunge them into deep trouble depending on which planet is controlling him and which bhava or pattern of life he is aspecting. Good or evil for the person? As explained, it depends. Ketu on the other hand is considered responsible for moksha, sannyasa, and self-realization. Anyone under the influence of Ketu can achieve great heights, most of them spiritual.

In his 1991 book, ‘Gods, Sages and Kings’, Frawley explains that Asura is in fact one of the main names of the Divine in the Rig Veda, second only in fact to Deva, and can be applied to any of the Vedic gods; although it is more specifically employed for the Adityas, solar divine forces, notably Varuna, who determines karma. Worship of the Asuras was important for the warrior class of Kshatriyas. Page 264:

In the Vedic era when the Brahmins and Kshatriyas, the priests and warriors, remained primarily in harmony, Asura was equal with Deva as meaning the Divine. Later, when the Brahmins and Kshatriyas quarrelled, which conflicts begin in the Rig Veda itself, Asura came to mean demon.

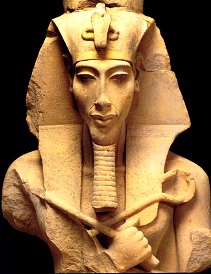

The Egyptian pharaoh Akhenaton has been accused of inventing monotheism, with his insistence on worshipping the Sun. But this was a mere aberration. In any case, the gods of Egypt themselves died, even if they were resurrected.There was no concept of eternal damnation.

The Egyptian pharaoh Akhenaton has been accused of inventing monotheism, with his insistence on worshipping the Sun. But this was a mere aberration. In any case, the gods of Egypt themselves died, even if they were resurrected.There was no concept of eternal damnation.

However, there was an implicit dualism in the contrast between the god Seth and the god Osiris. Seth, a violent, aggressive, “foreign,” sterile god, connected with disorder, the desert, and loneliness, was opposed to Osiris, the god of fertility and life, active in the waters of the Nile.Seth’s personality was ambivalent; and, as a typical trickster, he was also capable, at times, of constructive action in the cosmos. Seth or Set is often claimed to be the forunner of the Hebrew and Arabic, Shaitan.

But he was no irredeemable Satan. He killed and dismembered Osiris and sexually abused that god’s consort Isis, as well as son Horus. But Seth was needed to balance order in the cosmos.

In ancient Mesopotamia, myths pertaining to the origin of the gods and of the cosmos, the opposition between the primordial deities (Apsu, the Abyss, and Tiamat, the Sea) and the new ones (particularly Marduk, the demiurge, or creator) displayed some dualistic aspects. For the ancient Sumerians, the very nature of man as evil. Gerald Messadié in his 1993 book ‘A History of the Devil’, page 108:

Mesopotamia invented sin to abase the individual, and worse yet, so that the individual would justify his own abasement to himself. Iran, meanwhile had invented the Devil to terrify him. The beds of our “demonized” monotheisms were made; all that was left now was for them to lie down.

Why Iran? Ancient Iranian religion had much in common with the Vedic. Indeed fire remains sacred to the Zoroastrians today, many of whom sought refuge in India when their own ancestral land of Iran went Islamic.

Ancient Iran was inhabited by Elamites, Medes and Persians (Iranians). It was at the crossroads of ancient civilisations and many cultures.While Vedic influence from the east was no doubt pronounced, to the west there were the ancient civilisations such as Egypt, Babylonia, Phoenicia, Hittites, Armenia, and an aggressively expansive empire of Assyria.

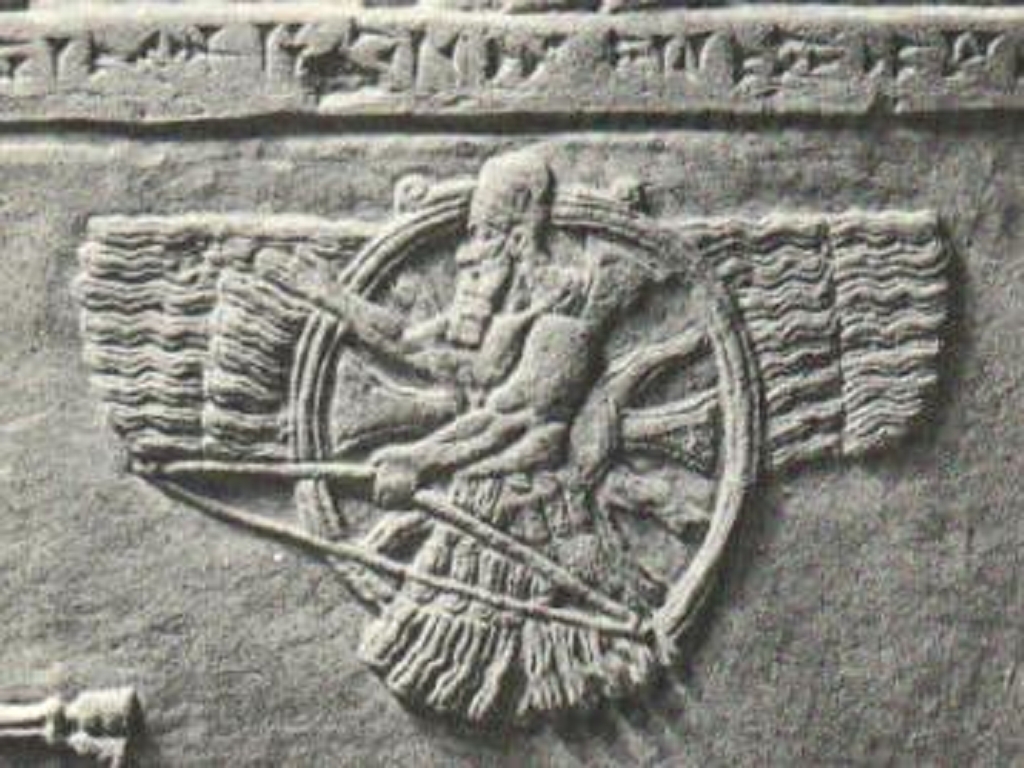

The Assyrian kings ruled as representatives of their warlike god Ashur. They were the deity’s earthly instrument and felt it their duty to impose his worship on the whole world. The enemies of Assyria were therefore the enemies of this god.

The Assyrian kings ruled as representatives of their warlike god Ashur. They were the deity’s earthly instrument and felt it their duty to impose his worship on the whole world. The enemies of Assyria were therefore the enemies of this god.

The massacres, deportation and mutilation characteristic of Assyrian warfare were justified in this coalescing of political and religious ambition into what were perhaps the first proto-monotheistic crusades.

It was this that marked ‘Ashurism’ as a different type of religion. All gods were seen as subordinate to this dominant Ashur, symbolised as a deity in a winged and emanating sun disk. Interestingly, earlier depictions didn’t include the deity, but only the winged and emanating sun disk. Ashur’s consort was Ishtar or Astarte: the goddess of love, war, fertility, and sexuality.

In the Egyptian religion Ashur was identified with Amun-Ra. Both gods were identified as the king of the Gods. In the ancient Cannanite religion Ashur is equated with Yahweh whom was depicted as a man sitting in a winged chariot. Yahweh’s consort Asherah or Astartu is commonly equated with Ishtar.

In Zoroastrianism, Ashur is equated with Ahura Mazda. Indeed in the art of the Achaemenid Empire and both Ahura Mazda and Ashur were depicted with almost the exact same iconography. Frawley on page 268 of ‘Gods, Sages and Kings’:

The ancient Assyrians also worshipped Asura. In fact they derived the name of their main city and their whole culture from that of their main God Ashur. Assyrian Ashur, like the Vedic Asura, was a Sun God and a militaristic God of great power and victory. Like the Persian Ahura and Egyptian Sun God he was symbolized by the winged disc.The Assyrians were more typically a Kshatriya dominated culture, a militaristic culture of war, conquest and empire.Certainly the terrible reputation of military power fits very well with the Vedic idea of the aggressive and violent Asuric nature that came to be associated with this name.Hence there can be little doubt that the terrible Asuras we read of in the Vedas, insofar as they have an historical counterpart, were not the Persians, who were close to the Vedic culture, but the Assyrians.

What did this mean at the practical level? AL Basham in the introduction to his classic 1954 book, ‘The Wonder that was India’:

The ghastly sadism of the kings of Assyria, who flayed their captives alive, is completely without parallel in ancient India. There was sporadic cruelty and oppression no doubt, but, in comparison with conditions in other early cultures, it was mild. To us the most striking feature of ancient Indian civilization is its humanity.

That had much to do with Asuric types of mysticism being regarded as inferior to the Devic. But what would happen if this concept was inverted and turned on its head? This is exactly what happened to bring the counter-god, Satan, or the Devil into the world.

One True God

In Chinese philosophy, traditional medicine, spirituality and more broad thought, the concepts of yin and yang dominated. Yin and yang describes apparently opposite or contrary forces are actually complementary, interconnected, and interdependent in the natural world, and how they give rise to each other as they interrelate to one another.

Yin is characterized as slow, soft, yielding, diffuse, cold, wet, and passive; and is associated with water, earth, the moon, femininity, and night time.

Yang, by contrast, is fast, hard, solid, focused, hot, dry, and aggressive; and is associated with fire, sky, the sun, masculinity and daytime. But it is not simply a dualistic antagonism between good and evil. Statecraft, the spiritualism in Taoism, the social order with Confucianism, and scientific enquiry such as research into earthquakes, was to find the correct balance between these two cosmic elements.

The ancient Iranians or Persians called themselves Aryan, just like the Vedic peoples. Iran in fact comes from the root term. But by a sound shift in language, Asura became ‘Ahura’, and the main name for the Iranian deity of righteousness and creator of the universe, Ahura Mazda.This was the Iranian equivalent of Varuna and Mitra. Zoroastrian practices include fire worship with chants to deities Vrethragna (Indra), Atar (Agni) and Homa (Soma).

The ancient Iranians or Persians called themselves Aryan, just like the Vedic peoples. Iran in fact comes from the root term. But by a sound shift in language, Asura became ‘Ahura’, and the main name for the Iranian deity of righteousness and creator of the universe, Ahura Mazda.This was the Iranian equivalent of Varuna and Mitra. Zoroastrian practices include fire worship with chants to deities Vrethragna (Indra), Atar (Agni) and Homa (Soma).

The ancient Iranians also identified Rama with Vayu. Yama was Yim, the primeval king who rules for 1800 years and was later called Jamshid in the Shanameh chronicle of kings compiled by Firdausi in c.1010AD. Yim later becomes ruler of paradise.

But Deva became ‘Daeva’ or ‘Div’, the demonic force. Iranian beliefs also feared other evil beings such as sorcerers and magicians whop controlled evil (the yatu), and fairies (paraika) who seduced and harmed men.The god Mithra battled the divs and paraika. Ahura Mazda created the universe.

He had summoned time and creation into being. But he is opposed by Angra Mainyu or Ahriman, the Evil Spirit which tries to destroy the worlds and harm men.Ahura Mazda had engendered Arta, or Truth, to give order to the universe. But Arta was shadowed by Draugu, the Lie. Angra Mainyu lived in the north of Iran, and to mislead and harm humanity he takes the form of a lizard, snake or youth.

He had summoned time and creation into being. But he is opposed by Angra Mainyu or Ahriman, the Evil Spirit which tries to destroy the worlds and harm men.Ahura Mazda had engendered Arta, or Truth, to give order to the universe. But Arta was shadowed by Draugu, the Lie. Angra Mainyu lived in the north of Iran, and to mislead and harm humanity he takes the form of a lizard, snake or youth.

He is helped by the demon of fury and outrage known as Ashma, and the three-headed monster Azhi Dahaka. In the ensuing cosmic battle, it is the warrior god Verethragna who dispenses divine justice and uses his mace against Angra Mainyu and the humans he misleads.

According to the Shahnameh, Jamshid (Yim) became arrogant and abjured his homage to Ahura Mazda. Ahriman was thus able to gain supremacy and usher in an era of darkness, with the rule of Zahhak. This new king was tempted by the Devil to murder his father, after which two snakes grew from each shoulder, respectively.

These snakes needed to be fed humans daily. Firdausi identifies Ahriman or Angra Mainyu as the Devil in his chronicles. In this he was obviously trying to fit in ancient Iranian beliefs within the now dominant Islamic narrative, not least for his patron Sultan Mahmud Ghaznavi. But how much truth is there to this Iranian proto-monotheism, and above all this emergence of a clear all-encompassing Evil ‘One’?

![]() The Achaemenid dynasty was the first great Persian or Iranian empire. Inscriptions from the period show Emperor Darius making reference to cosmic turmoil due to the presence of evil which contradicts the dominance of Ahura Mazda.The Achaemenids placed themselves as the centre of Aarta (Order of Righteousness) and Drauga (the Lie).

The Achaemenid dynasty was the first great Persian or Iranian empire. Inscriptions from the period show Emperor Darius making reference to cosmic turmoil due to the presence of evil which contradicts the dominance of Ahura Mazda.The Achaemenids placed themselves as the centre of Aarta (Order of Righteousness) and Drauga (the Lie).

Darius as regent of Ahura Mazda, is thus the enemy of evil. When the Elamites rose in revolt in 520BC, he condemned them for not worshipping Ahura Mazda.His victory thus sustained the cosmic order in which he ruled by divine right from this Creator. Inscriptions by Xerxes denounce the worship of daevas as unacceptable, because these ‘false’ gods confuse.

An inscription at Persepolis records how Xerxes destroyed a daivadana, or ‘place of daivas’, establishing the worship of Ahura Mazda in its place. However this is by no means uniform.

During the reign of Artaxerxes II (405-359BC), inscriptions at Susa mention Anahita and Mithras after Ahura Mazda. Anahita was identified with the Babylonian goddess Ishtar. Babylonian historiographer Berossus says that he erected statues to Aphrodite in Babylon. The same commentator claimed that the Medes and Persians did not worship images of wood or stone.

During the reign of Artaxerxes II (405-359BC), inscriptions at Susa mention Anahita and Mithras after Ahura Mazda. Anahita was identified with the Babylonian goddess Ishtar. Babylonian historiographer Berossus says that he erected statues to Aphrodite in Babylon. The same commentator claimed that the Medes and Persians did not worship images of wood or stone.

The empire of Darius and Xerxes threatened Greece for centuries, and was well known to the latter.

Plutarch wrote that Artaxerxes II inaugurated priests in the sanctuary of a “warlike goddess” he identified with Athena. Yet he also speaks of the Persian dichotomy of Good and Evil, between the god (theos) Oromoazes and the spirit (daimon) Areimanios. The former was born from the purest light, and latter from “darkness and ignorance” creating rival gods and introduced evil. Jenny Rose, associate professor of religion at Claremont Graduate University, in her 2011 book ‘Zoroastrianism: An Introduction’, page 75:

His account provides us with a comprehensive description of Zoroastrian cosmology, which is not presented systematically in any explicit Iranian text until the Middle Persian Bundahishan. In the Bundahishan, Ohrmazd (Ahura Mazda) creates the world in two stages of the 3,000 years, first in its menog state including all the spiritual beings needed to combat evil, then its getig state.After this period, Ahriman (Agra Mainyu) pierces the world at Nav Ruz and ‘rushes in’, mingling evil with good.This time of ‘mixture’ lasts for another 6,000 years, but the advent of Zarathustra at the end of the third millennium sets the scene for the final period of battle, and the ultimate separation of good and evil.

Aristotle also attempted to understand the beliefs of this most implacable foe of Greece. He wrote on how the magi (priests) believed in two opposing forces. The good spirit (daimon) called Oramardes which he identified with Zeus.

This was countered by Areimanios which Aristotle identified with Hades, god of the gloomy underworld guarded by three-headed dog Cerberus. Tom Holland in his 2005 book ‘Persian Fire’, which traces the wars between the ancient Greeks and Persians, explains this fusion by Darius of a unique cosmic, moral and political order, on pages 55 and 56:

This condemnation of a people for their neglect of a religion not of their own, was something wholly remarkable. Until that moment, Darius, following the subtle policy of Cyrus, had always been assiduous in his attention to foreign gods. Now he was delivering to the subject nations of the world a stern and novel warning.Should a people persist in rebellion against the order of Ahura Mazda, they might expect to be regarded not merely as adherents of the Lie but as the worshippers of ‘daivas’ – false gods and demons. Conversely, those sent to war against them might expect ‘divine blessings’ – both in their lives, and after death’.Glory on earth and an eternity in heaven: these were the assurances given by Darius to his men.The manifesto proved an inspiring one. When Gobryas, Darius’ father-in-law, led an army into Elam, he was able to crush the revolt with a peremptory, almost dismissive, speed. Never again would the Elamites dare to challenge the awful might of the Persian king. Such was the effect of the world’s first holy war.

Darius claimed that Ahura Mazda had anointed him as king, as found by inscriptions on his tomb at Naqsh-i-Rustam. Cyrus on the other hand, on the famous Cylinder named after him, is depicted as king of Babylon, divinely sanctioned to rule by the Babylonian god Marduk.

Darius claimed that Ahura Mazda had anointed him as king, as found by inscriptions on his tomb at Naqsh-i-Rustam. Cyrus on the other hand, on the famous Cylinder named after him, is depicted as king of Babylon, divinely sanctioned to rule by the Babylonian god Marduk.

He also claimed the right to rule by identifying himself with the previous rulers of not just Iran, but also Akkad and Sumer, states which had predated Babylon in Mesopotamia. Darius claiming that he was anointed by none other than Ahura Mazda himself was indeed influenced by this Mesopotamian idea of the king being the deity’s regent on earth.

In ancient Iran, according to Gerald Messadié in his 1993 book ‘The History of the Devil’, the Ahuras were once the higher deities, and the daevas were lesser ones. Ruled by Ahura Mazda and Mithras, the Iranians originally had no concept of an all-evil ‘counter-god’. Mithra acted as celestial intermediary between Ahura Mazda and Angrya Mainyu. On page 77, Messadié tries to explain the seismic shift which took place:

One fundamentally Vedic belief, however, that of salvation, an entirely new idea in the history of religions, suddenly came to assume great importance. (the Devil found as fertile ground in this theme as a bacteria culture might in a petri dish – because if you say “salvation” you also say “damnation”, and once you’re saying “damnation” you’ve already said “The Devil”).In Sarmatian and Alanic theology – the theology of the Scythians is little known – we for the first time witness the appearance of the irrevocable judgement over a dead person’s soul. In the Ossetian funerary ceremony, the bahfaldisyn, a participant speaks out to recall that the soul of the deceased which has left on horseback for the land of the heroes, the Narts, must cross a narrow bridge, the Shinvat Pereta or “Bridge of the Petitioner”. If his soul is righteous, he will cross; if it is not, the bridge will collapse under him and his mount.

The god Rashu decides the soul’s fate. The sinner goes to an infernal place of flames and noxious smells, the Hamestagan. This abode will vanish with the universal resurrection of the Last Judgement.

Ahriman however was Ahura Mazda’s twin. He was also emergent from Infinite Time. He was not Ahura Mazda’s inferior. He was honoured for having created the physical world. What changed?

The Creation of Satan

The sacred texts of ancient Iran, known as Gathas, were said to have directly come from Ahura Mazda. But this was via an intermediary a Chosen One, the mouthpiece. This was Zarathustra. On the basis of the Gathas, Zarathustra lived around 1100BC. He is said to have challenged the existing beliefs, such as those in the gods of Mithras, Mah (moon), Vayu (wind) and Atar (fire).He condemned the use of homa (soma) in sacrifice.

The sacred texts of ancient Iran, known as Gathas, were said to have directly come from Ahura Mazda. But this was via an intermediary a Chosen One, the mouthpiece. This was Zarathustra. On the basis of the Gathas, Zarathustra lived around 1100BC. He is said to have challenged the existing beliefs, such as those in the gods of Mithras, Mah (moon), Vayu (wind) and Atar (fire).He condemned the use of homa (soma) in sacrifice.

Instead there was war between Ahura Mazda and Ahriman, which the latter would lose in the eventual judgement day. While humanity had free choice, paradise awaited the righteous, while a dark forbidding hell was the destiny of those tempted by Ahriman.

The Gathas teach that at genesis of the cosmos there were two spirits: Ahura Mazda chose good, Ahriman chose evil. Indra-vayu became the god of death. Messadié explains on page 84 that now there is definite good and evil dichotomy:

Ahroman’s malevolent servants include Azaziel, the demon of wild places, who is incarnated as the Goat and as such transmitted wholesale to Judaism; Leviathan and Rahab, demons of chaos; and the pathetic Lilith whose legend also adopted into Judaism, holds that she was the barren first wife of Adam whose rejection at the hands of the First Man impels her to rage around at night, seeking revenge. Whether Jewish, Christian or Muslim, we are still living with this heritage; we still know these demons.

It is with the advent of Zarathustra that we get the germs of monotheism. Page 83 and 84 in Messadié’s book on the Devil:

The one and only true god worthy of veneration became Ahura Mazda. The ancient god Indra was reduced to the rank of demon, as were the “Secondary” deities, the Nasatya twins. According to the Gathas, Ahura Mazda is the creator of Heaven and Earth, of the spiritual and material worlds.He is the sovereign, lawmaker, supreme judge, master of day and night, the creator of nature, and investor of moral law. It would be hard to describe the God of the three later monotheisms any better. The relationship among Mazdism, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam is obvious.

Zarathustra proclaimed Ahura Mazda as the uncreated spirit, wholly wise, benevolent and good, as well as the creator and upholder of Asha (“truth”). While fetching water from dawn for a sacred ritual, he saw the shining figure of the yazata Vohu Manah, who led him to Ahura Mazda, where he was taught the cardinal principles of the true religion. Ahura Mazda was the only spirit worthy of worship and created the yazatas to aid him.

Zarathustra proclaimed Ahura Mazda as the uncreated spirit, wholly wise, benevolent and good, as well as the creator and upholder of Asha (“truth”). While fetching water from dawn for a sacred ritual, he saw the shining figure of the yazata Vohu Manah, who led him to Ahura Mazda, where he was taught the cardinal principles of the true religion. Ahura Mazda was the only spirit worthy of worship and created the yazatas to aid him.

The term ‘yazata’ itself comes from the same Avestan (old Persian) root as ‘yasna’, which refers to acts of worship, and is identical in root to the Vedic Sanskrit ‘yajna’: however the latter refers to using fire, while the yasna uses water.

The daevas or divs by contrast were evil spirits, created by Angra Mainyu or Ahriman, who is inferior to Ahura Mazda.In the texts of the Younger Avesta (composed many centuries after the Gathas), Zoroaster is depicted wrestling with the daevas and is tempted by Angra Mainyu to renounce his thinking (Yasht 17.19; Vendidad 19). Simon Pearson, head of English at a tutorial college in London, wrote ‘The End of the World’ in 2006, in which he looked at ideas regarding an impending apocalypse. Page 21:

According to tradition, it was at the age of thirty that Zoroaster underwent a revelatory experience while drawing water on the banks of the Daitya river. An angelic figure appeared to him and led him into the presence of Ahura Mazda – a deity that is wholly wise, just and good.In the Zoroastrian faith, Ahura Mazda is the creator of asha, an all-embracing order.From the stars in the firmament, to the waters down below, to the separation of light and dark, to sons being respectful towards their fathers: all these are manifestations of the divine order. However, Ahura Mazda has an evil twin, the ‘Hostile Spirit’, Angrya Mainyu.The two brothers are locked in a permanent conflict as they battle for supremacy. This bad case of sibling rivalry will last until the end of time. Only then will there be an ultimate triumph of good over evil, Ahura Mazda over Angra Mainyu.

Zarathustra was said to have converted the local ruler Vishtashpa, the father of Darius I. But his dichotomy of good and evil was only established gradually. Nevertheless it was to prove toxic. Messadié on page 85:

His theological conception of the world is so close to that of Christianity that one wonders if the church Fathers hadn’t read the Gathas or even copied them: life is only a passage in which each thought, word and action determines the individual’s fate in the hereafter, when the god of Good will punish the wicked and reward the virtuous.When the incarnated Mithra defeats Ahriman at the end of time, the dead will be resurrected; the Last Judgement will condemn the bad to Hell, while the good will live in Paradise for all eternity. The framework of the three monotheisms had been erected. The Devil’s birth certificate was filled out by an Iranian prophet.

Zarathustra introduced the idea of a saviour, Saoshyant, who would lead the forces of light and good against the evil and malevolent elements at the end of the world. Eventually, Ahura Mazda will triumph, and his agent Saoshyant will resurrect the dead, whose bodies will be restored to eternal perfection, and whose souls will be cleansed and reunited with this Supreme God.

Time will then end, and asha and immortality will thereafter be everlasting. The echoes of this found in Judaism, Christianity and Islam are unmistakeable. It certainly fed into what became Christianity. Writer and filmmaker Sean Martin from his 2010 book, ‘The Gnostics’, pages 24 and 25:

Zoroastrianism also has a unique solution to the problem of evil, In its traditional form, the Good Religion holds that there is one good god, Ahura Mazda (Wise Lord), under whom are the two equal twin forces of Spenta Mainyu (the beneficient or holy spirit) and Angra Mainyu (the hostile or destructive spirit).Alhtough Ahura Mazda’s creation is good, the source of all evil within it is caused by Angra Mainyu, who is destined to be overcome at the end of historical time, at which point eternity will begin.

Classical Zoroastrianism, however, underwent changes as the fortunes of the Persian Empire rose and fell. Over time, Ahura Mazda became identified with Spenta Mainyu, reducing the original trinity to a binary pairing.The names of the Wise Lord and his adversary also underwent transformation, being contracted to Ohrmazd and Ahriman, respectively.

By the time of the Achaemenid Dynasty (550-330 BCE), Ahroman was no longer seen as being created by, and inferior to, Ohrmazd, but was now regarded as his equal.Again, this concept of two gods would resurface in Gnosticism, where the true God remained outside the world of matter, while the creator God was seen as arrogant and inefficient. This god came to be identified with the God of the Old Testament, suggesting that some elements within Gnosticism may have been rebelling against their Jewish heritage.

The Jews were returned from exile in Babylon to their homeland by Cyrus, who is thus lauded in the Book of Isiah in the Bible. He is seen as an instrument of Jehovah, Yahweh, the Lord, and the one true God. Hence what became Judaism may well have inherited its dualism from Iranian religion. The Israelites had been deported and enslaved due to breaking the divine covenant.

The Jews were returned from exile in Babylon to their homeland by Cyrus, who is thus lauded in the Book of Isiah in the Bible. He is seen as an instrument of Jehovah, Yahweh, the Lord, and the one true God. Hence what became Judaism may well have inherited its dualism from Iranian religion. The Israelites had been deported and enslaved due to breaking the divine covenant.

Iran had liberated them. Hence the receptiveness to Iranian beliefs by the survivors. In this context, Ahura Mazda could easily be seen as God and Ahriman as the Devil. Messadié argues that the idea of the Devil as enemy of God was alien to Judaism, until adopted and magnified by the apocalyptic visions of the monastic Essene sect, brought to world attention by the Dead Sea Scrolls. Page 340:

The Devil of the Iranian Zoroaster could not have been settled so easily on the banks of the Dead Sea had the ground there not been prepared for him – as it had been, by the Mesopotamians in general and the Babylonians in particular. It was not only the scheme of Genesis and the Ten Commandments, to name just two, that Judaism borrowed from Mesopotamia; it was also the notion of sin inextricably associated with penitence, as well as the association of woman with the Devil.

While many are ready to accept that the concept of Absolute Evil, Satan, the Devil, Lucifer or whichever term is used in the three monotheistic faiths of Judaism, Christianity and Islam, had its source in Zarathustra’s dualism, it would be disturbing to realise that this goes far beyond what is termed ‘religious’.

Modernism with its post-Enlightenment dualism bifurcates the world into spiritual and temporal, sacred and profane, religious and secular, the idea of the Devil and Absolute Evil transcends all that.Which is why when western political and social commentators tout the forces of ‘good’ and ‘moderation’ they are at a loss to explain why these same elements of ‘progress’ morph horribly into the ubiquitous ‘evil’ and ‘extremism’.

If one side must be good the other has to be evil, under various verbiage and labels that are used. This is only possible due to the existence of the Devil who has now become an integral part of western thought, political, religious or secular. John Gray, ‘Black Mass’, page 12:

It was the belief in a cosmic war between good and evil, a belief that had animated Jesus and his disciples, and which echoed the dualistic world-view of Zoroaster. Through its formative influence on western monotheism – of which Islam and modern political religions are integral parts – Zoroaster’s view of the world shaped much of western thought and politics. When Nietzsche declared that good and evil are an invention of Zarathustra he may have been exaggerating, but he was not entirely wrong.

Also read

We Are Spirits In The Monotheist World : Part One

‘ We Are Spirits In The Monotheist World ’ : Part Two – Good Vs Evil