Launceston Examiner (Tas.: 1842 – 1899), Thursday 12 April 1877, page 3

PROPOSED HINDOO MISSION TO AUSTRALIA. A HINDOO’S OPINION OF TASMANIA (From the ‘Benares Light’, a Hindoo journal)

A meeting of influential Hindoos was held in Benares, to listen to an account of a visit paid by Kaboo Surajee to the Australian colonies, and to receive a proposition to form a Hindoo Missionary Society for these countries. The chair was taken by Maharaja Hyder Sawib who opened the proceedings by welcoming the distinguished traveller, referring to the depraved habits of many of the Europeans in India, and Strongly urging upon his countrymen to avoid such habits.

He said he had much pleasure in introducing to them their countryman Surajee, who had just returned from a tour in those interesting British colonies in the Southern seas, which are known as Australia. Kaboo Surajee, who was received with considerable expression of feeling by the audience, stated that his object in undertaking his recent tour was the desire of becoming acquainted with British institutions and habits, and which knowledge he thought he could acquire in some measure by visiting the colonies, although he should have liked to have paid a visit to England ; but which he was deterred from doing by the fear that his health would not be able to stand the climate of that country, and he resolved to go to the more sunny climes of the colonies, and by no means regretted having done so.

For in the first place, he was astonished at the rapid progress which these new colonies have made. They had sprung up into life and attained a growth as rapid as many of the plants and trees of India’s fair land. He would here say that he went about in a very unpretentious way, for had it been known that he was a foreigner, he would in all probability have been “lionised” as the colonists are in the habit of making much of foreigners, especially if they are presumed to be wealthy, and bear a title such as “Count Don”, &c.

Indeed, the possession of a foreign name will give an introduction into what he called “the best society” that is, into the society of persons who, what-ever may have been their caste originally, have made money, and have what is called “a good balance” at the bank. To prevent undue attention towards himself, he said he adopted the English style of dress, and assumed the name of Mr. John Smith.

Thus attired, combined with the fact that he was thoroughly acquainted with the English language, he was able to maintain his “incog.” as it is called, for, as he re-marked, he found many persons even among the upper classes with complexions quite as dark as his own. Through preserving his dis-guise, and having sufficient money at his disposal, he was able to stop at all kinds of inns or “hotels,” as they are called, from the most respectable down to the very lowest drinking den.

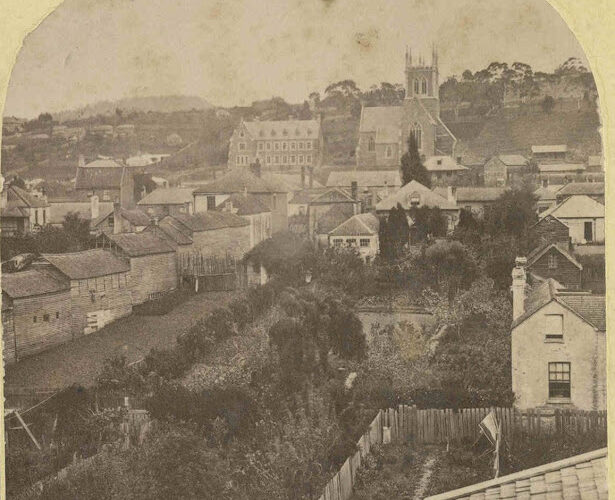

After describing, in the most felicitous manner, his visit to Queensland, New South Wales and Victoria, he proceeded to give an account of his visit to Tasmania. He observed that he had heard very much of the salubrity of the climate of that colony, and remembered, too, that it had been more that once proposed that the English soldiers should be sent there from India to recruit their health, and that some military officers with whom he had been acquainted in India had settled there. This induced him, he said, to cross the narrow sea which divides that colony from the continent of Australia. After giving a glowing description of the scenery of the country, as he passed from the north to the south, he described at considerable length the habits of the people as he observed them.

On arriving at Hobart Town, he said he put up at a hotel in one of the principal streets. From an early period in the evening to a late hour at night he stated that this place was frequented by young men well attired, who drank strong drinks and played at cards, although he was in0 formed that it was not lawful to have such cards in an inn. But the police never interfere. In-deed he was told that some of those who at-tended the place were councilors and justices of the civic Adalat, or court. He noticed many young men under the influence of drink, and who indulged in unchaste and profane language.

He also visited the low and poorer parts of the city, where he saw some of the most abject misery and poverty he had ever witnessed, and he observed that in those parts there were more drinking shops than in any other places. Every-thing in those neighborhoods bore the appearance of wretchedness and want. The dwellings were dilapidated and dirty in the extreme, and the children were wretchedly clad and filthy in person and played about in the gutters and filth which abounded there.

They seemed to be completely neglected by their parents many of whom he ascertained spent much of their time, and the money which they obtained, in the low public-houses. Another thing which struck his attention was the number of girls of immoral character found in the public streets, who, he believed, were in many instances the neglected children of drunken parents. The audience, he said, would naturally expect that he should endeavour to account for such a state of things existing in a country where Christianity is taught, and which its teachers claim as inculcating the highest morals of any system of religion. A variety of reasons, he observed, might be assigned for this.

For instance, the keepers of the drink shops are monopolists, the Government granting them, on the certificates of the magistrates or petty judges, the sole right to sell intoxicating drinks, for which they pay an annual tax. But he found, so far as the question of revenue was concerned, that the burdens imposed on the State by the crime and pauperism arising from intemperance, more than swallowed up the revenue derived from the monopoly.

Those who are interested in the maintenance of the liquor trade, such as brewers, publicans, and wine and spirit merchants, many of whom are very wealthy, use all their influence to keep up the present state of thing, and the priests or religious doctors do not as a body denounce the use of strong drinks; indeed, many of them partake of them. He found that great numbers of the people, especially those of the lower castes, never entered the temples or churches, where the Christian doctrines are taught, and the religious ceremonies are performed. He said that the people attending the church dressed as gaily as when attending the theatre, and the people who are impoverished by their drunken habits do not care to attend those places.

Indeed, it was quite clear from some cause or other, that the doctrines and laws of Christianity had either not reached the common people, any many of the upper castes, or else were not capable, of producing a high moral tone. Perhaps this was not the be wondered at, seeing that some of the highest of the priests taught that the Foundation of their religion was in the habit, when he dwelt on earth, of drinking the intoxicating liquor which he (the speaker) had seen to produce so much crime and misery among the English.

Nay, more, some of the priests went so far as to affirm that the Foundation of their faith miraculously turned pure and wholesome water into intoxicating wine! No wonder, said the speaker, with such teachings as these that the people indulged in these fiery liquors. To such an extent did the evil of drunkenness prevail that he had on different occasions seen priests, legislators, lawyers, shopkeepers and artisans under the influence of the poisonous liquors; and even the female sex was not entirely free from the evil.

The fearful state of things which he had thus witnessed had induced in him to come to the conclusion that it was their duty, as Hindoos holding the pure and sacred teachings of the Vedas, to do all in their power to raise such a noble people, as the English naturally were, out of their degradation, and he strongly advocated the formation f a Missionary Society, whose teachers should at once proceed to the Colonies of the Southern Seas, and endeavor to reclaim the poor besotted men and women there, as well as instruct the people on the great moral duties of life. He would do all that he possibly could in the matter.

He was prepared to translate into the English some of the most beautiful and elevating portions of the Vedas, and their Shastras, for circulation among the people. He knew several most excellent Brahmins and learned Pandits who were prepared to go out as missionaries, and it might afford them some encouragement to know that there were some few Nephalists in the Colonies, who follow the practices of the Arabian Rechabite, and who would probably become converts to their faith, inasmuch as he found that they had in their efforts to spread the principles of Nephalism and Rachabism, met with little or no tangible support from the priests and teachers of the Christian faith.

He strongly commended the scheme which he had proposed to his countrymen, and he believed they would do all that they could to carry out so noble and good a project. (Applause) Several speeches eulogistic of Kaboo Surajee were made, and it was unanimously resolved to carry out the plan he had suggested as soon as possible, and 6000 rupees were promised towards the object before the meeting closed.