There is a well-known observation among Hindu Activists Outside the Sangh that most of the usual performative academic experts on Hindutva haven’t probably heard about. Sita Ram Goel, the tallest of figures in that small but important category of Hindu Activists Outside the Sangh, observed, as early as the 1950s, that the typical reaction of a Sangh member was to remain sagely unresponsive when Hinduism is denigrated in their presence, but react instantly when the Sangh or its leaders are criticized. (Read the whole quote from that tallest living scholar for Hindus outside the Sangh, Koenraad Elst, here

There is a well-known observation among Hindu Activists Outside the Sangh that most of the usual performative academic experts on Hindutva haven’t probably heard about. Sita Ram Goel, the tallest of figures in that small but important category of Hindu Activists Outside the Sangh, observed, as early as the 1950s, that the typical reaction of a Sangh member was to remain sagely unresponsive when Hinduism is denigrated in their presence, but react instantly when the Sangh or its leaders are criticized. (Read the whole quote from that tallest living scholar for Hindus outside the Sangh, Koenraad Elst, here

Such a reaction, a massive collective eruption, indeed seems to have taken place across the world (or on phone  screens and zoom calls from across the world) in the last two weeks ever since a group of South Asia studies scholars and activists announced a “Dismantling Global Hindutva” conference around September 11, the anniversary of what is to some is a somewhat more monumental event than the allegedly more politically urgent “1/6 USA insurrection.”

screens and zoom calls from across the world) in the last two weeks ever since a group of South Asia studies scholars and activists announced a “Dismantling Global Hindutva” conference around September 11, the anniversary of what is to some is a somewhat more monumental event than the allegedly more politically urgent “1/6 USA insurrection.”

A conference demonizing Hindus… on 9/11 ! And announced around the same time the Taliban returned to power at that!

The outrage was not unexpected.

The most well-known of American Hindu advocacy groups, the HAF, initiated a letter campaign. Newer groups like COHNA followed up with their own actions. Well-known leaders and online activists hosted educational events and videos online. HAF, as of the time of writing, claimed that over 900,000 supporters signed on to its letters to the 40

The most well-known of American Hindu advocacy groups, the HAF, initiated a letter campaign. Newer groups like COHNA followed up with their own actions. Well-known leaders and online activists hosted educational events and videos online. HAF, as of the time of writing, claimed that over 900,000 supporters signed on to its letters to the 40  universities whose logos had been presented on the Dismantling Hindutva Conference announcement.

universities whose logos had been presented on the Dismantling Hindutva Conference announcement.

This conference was about dismantling Hinduism and therefore Hinduphobic, was the essential claim. The conference organizers, for their part, insisted that their critique was not against “Hinduism,” but against “Hindutva.” I will return to this distinction and offer my evaluation of it in a moment, but first, the relevance of the famous Goel quote here ,because it does contain an important lesson for everybody concerned.

Propaganda and Provocation: Decoding that Poster

As a student of media, I wonder first of all about what exactly might have caused such a quick and powerful reaction to this particular instance of perceived Hinduphobia among so many incidents that assault us daily, seen or unseen.

As a student of media, I wonder first of all about what exactly might have caused such a quick and powerful reaction to this particular instance of perceived Hinduphobia among so many incidents that assault us daily, seen or unseen.

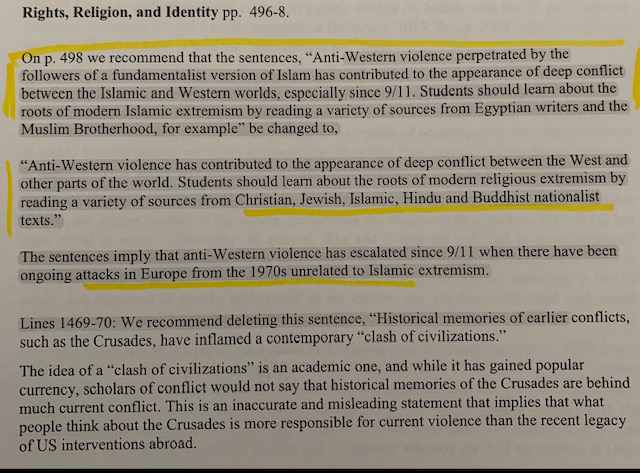

The timing of the announcement, the deeper polarization in the NRI/PIO community along political and even reality-lines, the feeling of being gaslighted consistently by an evasive and un-rigorous Hinduism/Hindutva distinction by academic experts, the timing of the conference announcement, and the timing of the scheduled conference itself (I should add here that the Hindu community is perhaps also familiar with an earlier initiative by several South Asia studies scholars to disassociate discussions of 9/11/2001 in the California school history curriculum with Islamic terrorism alone, and to include discussions of Hindu, Buddhist, and White Nationalist violence in the same context there).

All of this is relevant, but I have to wonder what it was about the conference poster itself that made it so provocative. The image on the poster, after all, respected the Hinduism/Hindutva distinction (at least within the logic of the South Asia Studies position at the moment).

It wasn’t a hammer to the gods or temples (though that has happened in the past, and indeed, happened just a few days ago apparently in Pakistan over a small boy’s micturition accident like a surreal Hinduphobic replication of an incident in Salman Rusdhie’s novel Shame). In the center of this poster was a hammer, extraction-end at that, offering to un-install a line of Swayamsevaks.

It wasn’t a hammer to the gods or temples (though that has happened in the past, and indeed, happened just a few days ago apparently in Pakistan over a small boy’s micturition accident like a surreal Hinduphobic replication of an incident in Salman Rusdhie’s novel Shame). In the center of this poster was a hammer, extraction-end at that, offering to un-install a line of Swayamsevaks.

And much like Sita Ram Goel’s 1950s observation, the threat of offence to the Sangh perhaps pushed a lot more buttons than any one incident in the past seven years or so. While thousands, perhaps tens of thousands of Hindus outside the Sangh, might be sincerely outraged and actively participating in the ongoing campaign against this conference’s perceived Hinduphobia, the fact remains that the RSS and its American cousins, and their peculiar way of doing and saying things, ought to remain on the table for an honest discussion as well.

After all, RSS leaders like Ram Madhav have tweeted about this issue (just as RSS leaders tweeted from India about how their karyakartas defeated the Leftists during the California textbook controversy, ignoring that many of the Hindu parents and scholars fighting for change were Hindus Outside the Sangh). Bloggers and columnists not formally identifying as Sangh members but with past associations such as the ABVP student group offered their recurring criticisms of American academics. Not surprisingly, they all got dismissed as Hindu “supremacists” by supporters of the conference (another appellation I will examine below).

After all, RSS leaders like Ram Madhav have tweeted about this issue (just as RSS leaders tweeted from India about how their karyakartas defeated the Leftists during the California textbook controversy, ignoring that many of the Hindu parents and scholars fighting for change were Hindus Outside the Sangh). Bloggers and columnists not formally identifying as Sangh members but with past associations such as the ABVP student group offered their recurring criticisms of American academics. Not surprisingly, they all got dismissed as Hindu “supremacists” by supporters of the conference (another appellation I will examine below).

It would be fair to say that the Sangh, and Hindu Activists Outside the Sangh, all “unitedly” rose in protest against the planned conference. Now I don’t deny the Sangh its right to defend its characterization in the public debate, and it should. I also don’t blindly condemn the eagerness of non-Sangh Hindus to see Sangh and Hindu interests as identical, though it is increasingly a question that should be discussed more candidly.

And I don’t blindly condemn most of my colleagues in American academia as they feel their academic freedom is under assault either (but my dissent against their actions remains; to a tenured first-world radical with a hammer, every heathen Hindu looks like a nail, perhaps). And to every Hindu fearing imminent extinction, Sanghi or otherwise, I ask the question: what exactly do you have in your toolkit by way of an alternative to what’s coming, what’s been coming at you, with deadly obviousness year after year?

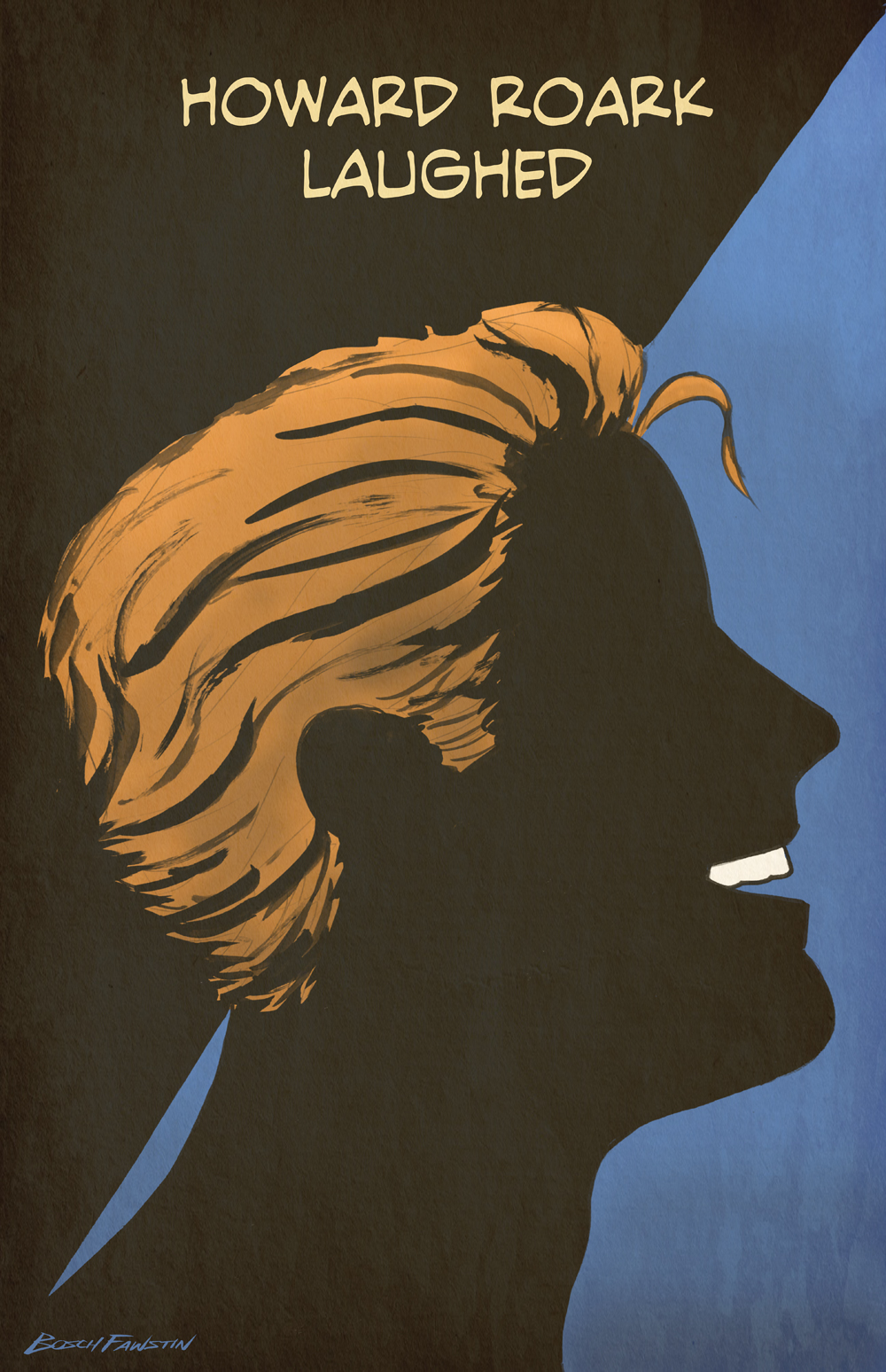

Howard Roark Laughed… with Hindus or at Hindus?

As an academic worker (I specify that for a reason) who has sought -mostly unsuccessfully- to build bridges between academia and the Hindu community in the past, what leaps out at me is the kind of narratives that dominate the present campaign against the DGH conference.

As an academic worker (I specify that for a reason) who has sought -mostly unsuccessfully- to build bridges between academia and the Hindu community in the past, what leaps out at me is the kind of narratives that dominate the present campaign against the DGH conference.

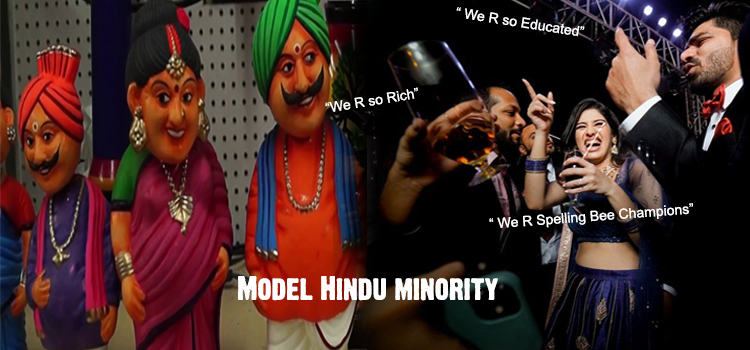

With a few honorable exceptions, what sticks out from the kind of things aggrieved Hindus are tweeting and talking about is their incredible sense of self-importance, status, and privilege in their approach to, well, my world, the world of the university; or, to be more specific, the rank-and-file academic workers who make up the university.

The whole thrust of the anti-DGH campaign so far has been not to recognize or support the emergence of dissenting or multiple views inside academia, but simply to flaunt one’s status and ties to the administration-side of the corporate university, the Big People at the top.

This trend was already brewing in the diaspora for a while before the conference drama began. For decades now, most of the Indian American community press has restricted its coverage of universities to the big-name big-money world of Indian-origin Deans, Vice Presidents, Chancellors and the like, and rarely covered the lives and work of more humble Indian academic workers and staff.

More recently, for India’s Independence Day, consulates reached out and got video-greetings from a number of University Presidents and Chancellors (and customary Important Indian-Origin CEOs). And then, when news of the conference came, diaspora leaders got busy right away right at the top where they felt they belonged, I guess. So far, so good? Maybe.

University officials, for their part, have responded to the protests in a limited set of ways; for the most, declaring their support for academic freedom while noting in some cases that the university logos were used by conference organizers without permission. Both sides, naturally see these developments as a sign of their victory, as online campaigns inevitably tend to do.

But the top-down approach in terms of university outreach is just one thing (and usually an unsuccessful thing, as most of the previous Hindu-Management-Bhai-Bhai stuff has been). What is even more revealing is the sort of thinking about class, status, belonging and American society that has emerged in the reactions of different Hindus to this issue.

One recurring element in many Hindu voices that protest against academia is their sense of disbelief that a “prestigious” big-brand university like Harvard or Yale would not be on their side. One tweet, for example, believes that “Hinduphobia is being created by a small set of mediocre academics in 2nd and 3rd tier Universities.”

One recurring element in many Hindu voices that protest against academia is their sense of disbelief that a “prestigious” big-brand university like Harvard or Yale would not be on their side. One tweet, for example, believes that “Hinduphobia is being created by a small set of mediocre academics in 2nd and 3rd tier Universities.”

This aggrieved Hindu perhaps did not see names like Columbia, Harvard, UCB, SOAS and others on the list of conference supporters! Another Hindu meanwhile tweeted that he was relieved to see Harvard seemingly distance itself from the conference because his son studies there.

What is more troubling though is that person, who presents himself as an  important leader of the Hindu community, has also boasted on Twitter that he was responsible for stopping the inclusion of Hinduphobia in legislation in the UK some years ago. This is a profoundly depressing example of the kind of ineptitude with which Hindutva organizations and their community leaders sabotage the Hindu community’s interests.

important leader of the Hindu community, has also boasted on Twitter that he was responsible for stopping the inclusion of Hinduphobia in legislation in the UK some years ago. This is a profoundly depressing example of the kind of ineptitude with which Hindutva organizations and their community leaders sabotage the Hindu community’s interests.

As someone who has seen America almost entirely through the lens of campus-life and campus-labor (when the minimum wage for cafeteria work was $4 an hour), I have never quite understood why the NRI community so quickly forgets the social and economic disparities that exist in society, the same sort of disparities which have long animated not only anti-Hindu activists and academics but often their own children too, who inevitably accept the South Asia studies canonical definition of NRI classism as Hinduism/Brahminism/Sanathana Dharma etc.

From the early 2000s when Hindu activism in America took off, to the present, the community has failed to make the slightest headway into the world of academia for this reason. It boasts about having arrived in society and in being fabulously successful, and floating Foundations and lobbies but doesn’t quite walk the talk. For an Ayn Rand-inspired, Right-Wing leaning, business-savvy group, it really doesn’t quite know the saying that you get what you pay for, or don’t pay for. Nor does it manage to demonstrate, on the other hand, that it is not the caricatured money and status-obsessed cult its own kids sometimes think it.

The harsh truth is that almost everyone in academia, or dare I say it, American society, knows that we are not a serious community. The line of what can be said or not said about Hindus has been steadily shifted in recent years against us towards absurdly racist levels without any serious reaction to the institutions where it needs to happen. To an objective observer, the anti-Hinduphobia outrage that occasionally erupts on Twitter now simply feels like a seasonal activity. A steady pulse of online cribbing is on constantly, occasionally erupting in petitions and some drama every few months with little change anywhere at all.

Hindus and Hindu organizations do not come across to anyone inside academia as people who are serious about truth in our institutions (and that’s the way it is now, there is no truth in most institutions, but unlike Hindus, others are fighting for it tooth and nail).

Hindus and Hindu organizations do not come across to anyone inside academia as people who are serious about truth in our institutions (and that’s the way it is now, there is no truth in most institutions, but unlike Hindus, others are fighting for it tooth and nail).

What Hindus come across as simply looking for a bit of image and recognition in their own community. I do not wish to be harsh. It is a sort of poverty of the soul in a society that slipped from primitivism to debauchery without civilization in between as it was once said (of America, I mean), and now, to total debacle too.

Hindu actions in relation to academia rarely look like anything more than an effort to get a nod from the Boss as good minorities over the heads of the delinquents and low-achievement losers they think infest academia, or at least the non-STEM areas. It should be eminently clear though by now to people that this country really has no boss. Neither Obama nor Trump nor Harris nor Pichchai’s names are going to scare off people who are fighting for their truth’s power over you, however untrue it may be.

Hinduism and Classism, Hindutva and Hinduphobia

The mental picture that many NRI Hindus, especially those in positions of some kind of leadership in the community, carry about their perceived foes (“the Hinduphobes”) thus seems to need some urgent, well, dismantling. What animates them comes across not really as pain for being unfairly, untruthfully, and often violently treated in a certain way simply for being Hindu.

The mental picture that many NRI Hindus, especially those in positions of some kind of leadership in the community, carry about their perceived foes (“the Hinduphobes”) thus seems to need some urgent, well, dismantling. What animates them comes across not really as pain for being unfairly, untruthfully, and often violently treated in a certain way simply for being Hindu.

Koenraad Elst’s summary in Decolonizing the Hindu Mind is an apt lesson, here:

“The very first Hindu grievance is that Hindus are being killed” and the second grievance is that “the killing goes on without anyone paying attention.” (p. 508)

This is such a clear message, but this is rarely what we manage to communicate. Instead, what we project is not informed and righteous rage against lies and violence but merely a tone of uppity annoyance at not being seen as the important, successful, high status achievers. In the past few years, I have heard one explanation come up time and again among NRI Hindus, and even some of their young adult children. They hate us because they are rich. They hate us because India is getting richer now with liberalization/development/Vikas etc.

This is such a clear message, but this is rarely what we manage to communicate. Instead, what we project is not informed and righteous rage against lies and violence but merely a tone of uppity annoyance at not being seen as the important, successful, high status achievers. In the past few years, I have heard one explanation come up time and again among NRI Hindus, and even some of their young adult children. They hate us because they are rich. They hate us because India is getting richer now with liberalization/development/Vikas etc.

Not only is this grossly uninformed by history (Hinduphobia, as recent research by Sarah Gates, has shown us, was seen as an obvious, self-evident reality by British anti-colonialists as early as the 1860s), but it also confirms the worst stereotypes that diaspora children have heard about their parents’ culture, traditions, and religions.

The cause of this status anxiety may or may not be “religion,” which may or may not even exist, per the general South Asia studies definition of “Hinduism,” but there’s only so much that other explanations can occur to children when parents themselves don’t care for them. Whatever image that the movie Slumdog Millionaire hammered  down about Hindus (like the nauseating quiz show host and others) as casteist, elitist money-worshippers, and Jamal and his brother as the cool alternatives to global capitalism (one totally cool, and the other redeemed by revolutionary violence in the end), that Anil Kapoor as Quizmaster is the image Hindus cling to even as they pick and throw words from here and there on the internet about colonialism, racism, and so on.

down about Hindus (like the nauseating quiz show host and others) as casteist, elitist money-worshippers, and Jamal and his brother as the cool alternatives to global capitalism (one totally cool, and the other redeemed by revolutionary violence in the end), that Anil Kapoor as Quizmaster is the image Hindus cling to even as they pick and throw words from here and there on the internet about colonialism, racism, and so on.

At this point, an anecdote worth sharing. A few years ago, a young diasporic film maker came to chat with me about my book Bollywood  Nation. He was working on a couple of ideas and one of them was about caste inequalities in India. The story involved the Brahmins of the colony being machine-gunned in the end. Not a surprising sort of idea in Indian creative and academic circles.

Nation. He was working on a couple of ideas and one of them was about caste inequalities in India. The story involved the Brahmins of the colony being machine-gunned in the end. Not a surprising sort of idea in Indian creative and academic circles.

So I told him about Vishwa Adluri’s work, and the roots of anti-Brahminism in colonial European religious prejudices, and the growing tendency of White American racists to hide behind the Brahminism ploy to hate on Hindus.

He heard me out with an open mind, and said the reason he wants to tell this story is that inequality pains him, that there are people like Jeff Bezos in this world. I said, then make a movie where the revolution targets the actual Billionaire Bozos running the world, not some poor or middle class easy-to-blame people from the third world who have been set up for centuries now by colonizers as excuses for destruction and plunder.

The diaspora is in a very complicated position because of race, class, caste, generational, professional (STEMBA v humanities/arts/activists) polarization. It is my growing realization that many of the problems that seem like Hindutva v Hinduphobia or Left v Right actually have much deeper causes, some of which have little to do with India or Hinduism even. But those social histories are for a different conversation.

For now, I wish to return, having identified I hope a serious lack in the Hindu community’s approach to academia, to the festering problem inside academia itself. A part of this problem is larger than its study of Hinduism or South Asia, and pertains to larger forces and shifts in the role and purpose of the university as it moves from “truth” to “justice” as its primary mission (a propos Haidt and others), and relies exclusively on a bureaucracy of identities to help deliver that promise. It overlaps with American liberal-conservative culture wars and that too is a whole other conversation because Indian immigrants as a relatively small and new immigrant group are hardly involved in either part of this debate. But there is one core issue that can be honestly sorted out by concerned academics I think, if they so desire: the Hinduism/Hindutva distinction, and by extension, the entrenched dismissal of Hinduphobia as a “Hindu Supremacist” fantasy.

I went through most of my doctoral studies in the 1990s with a clear assumption that I knew the difference between Hinduism and Hindutva. Hindutva was a word I never even heard in my extended family’s self-conception or conversation. I read about it mostly in the context of the English press’s coverage of the Ram Janmabhumi issue and the aftermath. It seemed to me in those days as mostly a political ideology, a desire to aggressively identify as Hindus and demonize Muslims as occupiers, invaders and so on. Hinduism, on the other hand, was the beautiful, cultural, spiritual world we grew up with. Hindutva was “Muslims should leave India and go to Pakistan,” and Hinduism was almost everything else. It was a simplistic understanding, and one that led me to even appreciate Anand Patwardhan’s work when he screened Father Son and Holy War in my college in the 90s.

Sometime between 2001 and 2008 (New York and Mumbai, and the aftermath of the discourse about Hindus in the media that followed), my views began to change. I expressed my concerns in my 2012 review essay Hinduism and Culture Wars that the alternative to conservative Hindutva that the South Asia canon was offering wasn’t really liberal Hinduism, but some sort of self-annihilation altogether. The distinction between Hindutva and Hinduism really wasn’t quite a well thought out one, it seemed.

You were either secular, or you were Hindutva (and of course Hindutva was more deadly than Al Qaeda as Martha Nussbaum wrote soon after 2001). Then, after Narendra Modi’s election as Prime Minister in 2014, a slightly different reconceptualization emerged (perhaps in response to books like David Frawley’s Hinduism for the Modern World, Hindol Sengupta’s Being Hindu, and my own Rearming Hinduism, I do not quite know). Shashi Tharoor boldly threw away the “Secularism versus Hindutva” characterization to try and own the word “Hindu” on its own, liberal terms. “Hinduism” versus “Hindutva” made its way into the conversation, and in the diaspora, American activists of South Asian heritage began to create organizations with names like Hindus for Human Rights and Sadhana, and scholars sought to propose Hindu liberation theologies and the like. This is the world and worldview which informs the Dismantling Hindutva supporters. They say they are not against Hinduism but only against Hindutva.

You were either secular, or you were Hindutva (and of course Hindutva was more deadly than Al Qaeda as Martha Nussbaum wrote soon after 2001). Then, after Narendra Modi’s election as Prime Minister in 2014, a slightly different reconceptualization emerged (perhaps in response to books like David Frawley’s Hinduism for the Modern World, Hindol Sengupta’s Being Hindu, and my own Rearming Hinduism, I do not quite know). Shashi Tharoor boldly threw away the “Secularism versus Hindutva” characterization to try and own the word “Hindu” on its own, liberal terms. “Hinduism” versus “Hindutva” made its way into the conversation, and in the diaspora, American activists of South Asian heritage began to create organizations with names like Hindus for Human Rights and Sadhana, and scholars sought to propose Hindu liberation theologies and the like. This is the world and worldview which informs the Dismantling Hindutva supporters. They say they are not against Hinduism but only against Hindutva.

If this was indeed true, why then has the distinction shifted so much? Why does “Hindus for Human Rights” never speak about Human Rights for Hindus? Surely, both can be done. Why do most of the examples of “Hindutva” or “Hindu Supremacism” that the average Hindu reader sees coming from the New York Times, Guardian, Economist, or Harvard, Berkeley, Yale, or Chicago, seem like an attack on just Hinduism, and not some recent political ideology that sprung up in its name (examples: New York Times on saris, Boston Globe on Modi’s reference to Navaratri fasting as a “wolf whistle,” virtually every Hindu festival, every Hindu god and even goddess…). Why do professors in UK get to target young female Hindu students and their families even on social media, or call for bans on H1B visas to Hindus? “Hindus don’t have human rights as Hindus” is the position, more or less, in the South Asia canon today.

If this was indeed true, why then has the distinction shifted so much? Why does “Hindus for Human Rights” never speak about Human Rights for Hindus? Surely, both can be done. Why do most of the examples of “Hindutva” or “Hindu Supremacism” that the average Hindu reader sees coming from the New York Times, Guardian, Economist, or Harvard, Berkeley, Yale, or Chicago, seem like an attack on just Hinduism, and not some recent political ideology that sprung up in its name (examples: New York Times on saris, Boston Globe on Modi’s reference to Navaratri fasting as a “wolf whistle,” virtually every Hindu festival, every Hindu god and even goddess…). Why do professors in UK get to target young female Hindu students and their families even on social media, or call for bans on H1B visas to Hindus? “Hindus don’t have human rights as Hindus” is the position, more or less, in the South Asia canon today.

And all of this is meant to not be questioned even. Because questioning, or even objective discussion, inevitably reveals what thousands of people can see with their eyes on social media coming from the gatekeepers of the Hinduism/Hindutva definition in academia. Sometimes, Hindus are the “White People of South Asia” and therefore cannot be a systemically oppressed people. Sometimes, Hindus are just “White People,” period, and German Nazism and US slavery is best explained by Manu Smriti (thank you, Oprah). Sometimes, Hindutva with its OBC Prime Minister Modi and Dalit President Kovind is casteism and must be smashed and sometimes Hinduism itself is caste-supremacism and must be annihilated.

Even in this age of i-phone addictions and fluctuating attention, people still have some brains left to see what is going on.

The Hindus v Academia Scorecard

There is one constructive thing though that can be done even in this age of dishonesty on one side, and delusional self-importance on the other. There is a conversation that can happen about the nature of power, privilege, pain, violence, and justice, indeed.

There is one constructive thing though that can be done even in this age of dishonesty on one side, and delusional self-importance on the other. There is a conversation that can happen about the nature of power, privilege, pain, violence, and justice, indeed.

But it cannot happen without some respect for the idea of truth, in every possible way. Hindu groups need to recognize truth in more practical terms. They don’t have the ability to make any change inside academia at the moment. Even if a million people sign a petition, what does it change in even one mind inside the university? Nine hundred professors who support DGH are going to continue to teach exactly what they believe in tomorrow, and in tens of thousands of student minds, papers, theses, dissertations, books, university and corporate policies, it’s their theories however absurd that will gain power.

And conversely, with the right kind of action aimed at their increasingly and visibly indefensible canon, nine hundred professors and their supporters can be made to return to the drawing board on some of their assumptions and positions. Yes, you can and should offer a critique of power in “South Asia.” But you cannot start that process without including yourself and your views in it.

The core point of dismissal of Hinduphobia in the South Asia academic canon today is the belief that there is no systemic oppression of Hindus as Hindus. Well, when they use the phrase “Hindu Supremacism” where is the evidence of systemic Hindu supremacism, “global Hindutva” at that? On the contrary, a close examination of the critical academic literature on Hindutva (and there’s a lot of it, contrary to claims made by some DGH defenders that Americans haven’t been educated enough about Hindutva), shows that the experts were rarely ready to honor the fig-leaf Hinduism/Hindutva difference they are hiding behind now.

Most academic experts on “Hindutva” after all do not begin with Savarkar or Golwalkar as they are now saying in their defense, but include Sri Aurobindo, Swami Vivekananda and Dayananda Saraswati as well. They include them through random quotes at best, rarely acknowledging the obvious and very relevant context of their Hindu re-discovery, revival, and yes, reform too; the context of Hindu subjugation under a real, global , racist, religious-supremacist colonialism. No wonder Hindus have started saying “Hindutva is Hinduism that Resists.” Hindutva experts have misrepresented most of India’s indigenous anti-colonial resistance from the 1600s to 1900s as “Hindutva,” adding-on some Golwalkar and Hitler patchwork later to their house of cards.

Most academic experts on “Hindutva” after all do not begin with Savarkar or Golwalkar as they are now saying in their defense, but include Sri Aurobindo, Swami Vivekananda and Dayananda Saraswati as well. They include them through random quotes at best, rarely acknowledging the obvious and very relevant context of their Hindu re-discovery, revival, and yes, reform too; the context of Hindu subjugation under a real, global , racist, religious-supremacist colonialism. No wonder Hindus have started saying “Hindutva is Hinduism that Resists.” Hindutva experts have misrepresented most of India’s indigenous anti-colonial resistance from the 1600s to 1900s as “Hindutva,” adding-on some Golwalkar and Hitler patchwork later to their house of cards.

As Sarah Gates recently tweeted, “no other community has the language that best defines their persecution explained away as a sign of their bigotry.”

And no other community twice-colonized by religious-racial supremacists gets its right to exist redefined as “supremacism.”

A Hindu guru (or “godman” as the cowards of colonial careerism sneer) might have said “Hinduism is the greatest religion,” sure, but that is at worst bragging, not a systemic power reality to warrant the academic fantasy label that is “Hindu Supremacism.” And most of the so-called “Hindu Supremacists” like Swami Vivekananda or Dayananda Saraswati who are smeared as such today said and did what they did while their lands, lives, temples, sacred animals, forests, everything was at the wrong end of a gun pointed by absolute stark raving fanatical mad supremacists spinning around the planet exterminating all difference in the name of their One (of two that is) True God.

A Hindu guru (or “godman” as the cowards of colonial careerism sneer) might have said “Hinduism is the greatest religion,” sure, but that is at worst bragging, not a systemic power reality to warrant the academic fantasy label that is “Hindu Supremacism.” And most of the so-called “Hindu Supremacists” like Swami Vivekananda or Dayananda Saraswati who are smeared as such today said and did what they did while their lands, lives, temples, sacred animals, forests, everything was at the wrong end of a gun pointed by absolute stark raving fanatical mad supremacists spinning around the planet exterminating all difference in the name of their One (of two that is) True God.

That was Hinduism as resistance. Indigenous resistance. Anti-dominionist, Nature-worshipping, animal god celebrating, and some-day planetary-uprising-leading resistance.

From the first Hindu temple destroyed by a Christian zealot in West Asia described by Sita Ram Goel, to the last Hindu temple priest staying on in Kabul this month despite everything, the memory of a 1000 year resistance is alive in the modern Hindu mind.

Academia must change, or fall.

And so too must the chief beneficiaries of the status quo of Hindu pain today, the messianic so-called Hindutva parties and their armchair activists.

And so too must the chief beneficiaries of the status quo of Hindu pain today, the messianic so-called Hindutva parties and their armchair activists.

Vamsee Juluri, Ph.D.

Professor of Media Studies, University of San Francisco

Author of Becoming a Global Audience: Longing and Belonging in Indian Music Television (Peter Lang, 2003), The Mythologist:A Novel (Penguin India, 2010), Bollywood Nation: India through its Cinema (Penguin India, 2013), Rearming Hinduism: Nature, Hinduphobia and the Return of Indian Intelligence (Westland, 2015), Saraswati’s Intelligence: Part 1 of The Kishkindha Chronicles (Westland, 2017) , The Firekeepers of Jwalapuram: Part 2 of the Kishkindha Chronicles (Westland, 2020) and The Guru Within (in progress).