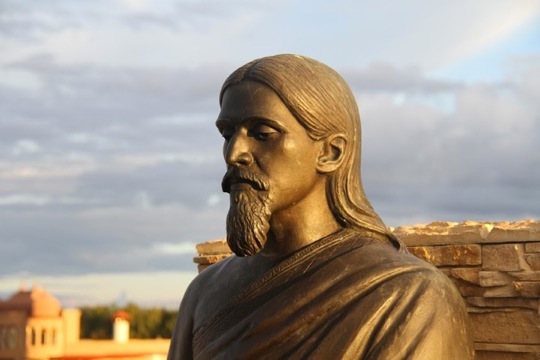

Before the spiritual Aurobindo, the political Aurobindo Ghose

While this is one of the rarer cases of a researched article on an Indian spiritual figure in the popular press, and is genuine, the discussion is somewhat superficial. Firstly, the general journalistic style of presenting opposing viewpoints on a subject, is not ideally suited to examining such a towering spiritual figure as Sri Aurobindo. By presenting some shallow views of the savant alongside informed critiques on the same footing, such an approach ends up legitimising ill-informed assessments.

The article begins well-enough, by quoting historian Sugata Bose:

“Half a century of indoctrination in the dulling ideology of statist secularism has led to profound misunderstandings of Aurobindo’s political thought and an utter inability to comprehend its ethical moorings,”

And then interestingly, goes on to amplify those very misunderstandings, by those very means – a lack of grounding in the hoary Indian tradition of philosophical enquiry. Sri Aurobindo’s political and spiritual thought, is certainly deeply rooted in the Indic paradigm and will not be understood from secondary readings. Firstly the concept of ‘Dharma’, which is certainly much more than ‘religion’, but is not also thus just a blanket term for ‘higher ethics’.

In the ancient Vedic view summarized in the Bhagavad Gita, dharma is the set of human choices and behavioural attitudes, that sustain the world by bringing about a dynamic equilibrium between various competing elements. Dharma is thus a manifestation in this world, of Rita, the wider spiritual and cosmic order, that sustains all life. For an ardent student of the Bhagavad Gita, as indeed many early Indian nationalists were, the struggle for emancipation of India from the clutches of colonialism was a direct call to Dharmic action – an adharmic external power was suppressing and subjugating the life force of a people and it was but Dharma to root them out.

It was neither Sri Aurobindo nor other leaders such as Bankim or Vivekananda who brought ‘religion into politics’ – rather religion was introduced into politics in India by the agents of the 2 large Abrahamic monotheistic religions – firstly when Arab and later Turkic-Mongol Islamic raiders launched religious wars involving orgies of violence and destruction at the behest of the Caliph himself, often sending back Qums from the loot. When the dust was settling following a few centuries of amiable rule under the Mughals, Protestant England came in, seeking to ‘civilize the heathens’ in the words of Rudyard Kipling who gave the necessary theological foundation for colonialism in India.

However from the beginning Indian resistance fighters only sought to correct this picture of externally inspired religious fanaticism by a dose of native Hindu spirituality. From the earliest of times, whether it was Bappa Rawal resisting the Turkics, or Jhulelal standing up for Sindhi Hindus or Vidyaranya inspiring Hari and Bukka or Samartha Ramdas to Shivaji, it was Hindu spiritual ( and not ‘religious’) leaders that led the counter-force. When fanatical religion seeks to divide the world into ‘us and them’, Hindu spirituality seeks to find that underlying thread of unity ‘from whom we arise, in whom we live and to whom we attain on death’. In fact before contact with the western partisans, perhaps there was no such concept of ‘religion’ in the greater Indian region.

In his fiery calls for youth to throw out the colonialists by invoking Hindu spiritual symbolism in such powerful concepts as the universal soul or ‘Vasudeva’ and quoting the Gita call to action, Sri Aurobindo was only following this illustrious tradition, drawing upon the common spirituality of the nation to unite the masses. His efforts presaged those of Gandhi later, who also attained a huge connection the collective consciousness of the nation through imagery such as that inherent in the ‘Rama Rajya’. They sought to and even succeeded sometimes, in uniting the whole of the subcontinent irrespective of religion, by appealing to the unique native spirituality that suffuses all religions in India.

It is for this reason that ‘spiritual nationalists’ such as Vivekananda and Aurobindo, could not see India under such narrow lenses as ‘Hindu’ and ‘Muslim’ – for the Hindu tradition teaches, that irrespective of the external form, the same spiritual yearning of man for the infinite informs all religious quest. It would therefore not be surprising if Sri Aurobindo assessed the Mughal empire favourably – for indeed this empire that came to be rooted in the spiritual ethos of India, even if its later potentates such as Aurangzeb were grossly partisan in their outlook and actions, was transformatively different from the ruthlessly fanatical Delhi Sultanates or the earlier Arab-Turkic raiders.

Indeed there is much to imbibe for today’s parochial nationalists, from this spiritual brand of nationalism, which alone perhaps has the key to unite India from Kashmir to Kanyakumari. For, at the heart of conflicts such as Kashmir or earlier Punjab, is the question of who stands better with the deeper essence of the people of those regions – an India that accepts the truth of inner unity despite apparent diversity, or a Pakistan that is ruthlessly crushing even differing shades of opinion within Islam such as the Ahmadi or Nizari.

The genius of Sri Aurobindo, was to link Yoga, or a conscious act of seeking union with the deeper and cosmic spiritual order in everyday life, with those calls to action for India’s freedom. If throwing out the British Raj was dharma, the act of defiance itself was also Yoga, for India in the spiritual-nationalist sense, was not just a territorial entity, but a spiritual being that through her hoary wisdom could yet benefit the vast majority of humankind lost in egotistical self-understandings. It was Yoga to fight for India’s independence, just as Sri Krishna had given Arjuna to understand, that it was Yoga to fight the Kauravas.

It was this very understanding that led him to seek seclusion later on in his life, working entirely by Yogic means to speed up the process of independence, and when that was certain, to move on to the collective spiritual evolution of mankind itself. Thus it is not a if Sri Aurobindo had a ‘former’ and ‘later’ life, and it would not be then surprising that he would be commenting on Indian politics during his supposedly spiritual phase – it was his singular journey to seek a solution to the problem of suffering in the world, just like the Buddha before, and the mission brought him to Yoga.

Also, just because Sri Aurobindo is not a Sankarite, that does not make his views European on the lines of figures such as Humbolt. White the Advaita Vedanta of Sankara is indeed one of the most lofty achievements of the native Indian genius, it is not its only representative. Much before, the Sarvastivada and Madhyamaka of the northern transmission lines of Buddhism achieved extraordinary understandings of human existence, managing to reach and enrich much of Asia and even Europe.

Within the schools of Vedanta itself, Advaita is only a cousin to other sister philosophies of Dvaita and Vishishta-advaita, which too have many legendary exemplars such as Ramanuja and Madhva and more recently Vallabha and Swaminarayan. More importantly, within Bengal there was the illustrious Vedantic school of Achintya Bheda-Abheda championed by the Vaishnavas including Srila Chaitanya. Indeed the dvaita-advaita or ‘advaita Isvaravadin’ schools of which the Bheda-abheda is an example, as quoted by Vivekananda, have such ancient teachers going back to the time of the Vyasa sutras, as acharya Bhaskara, and rather than being in the mould of scholars such as Humbolt, Sri Aurobindo’s spiritual thought is closer to and revives this ancient Hindu tradition of parallel and differing understandings of the Vedanta.

It is more likely and even by their own admission, that European scholars such as Deussen, Max-Mueller and Humbolt were influenced by such radical Vedantic thinkers who actually dominated the Hindu philosophical thought in medieval times much more than the Sankarites. Witness how the Vallabhites, the Natha-Yogis, Sant-panthis and all manner of Bhakti-Yogins were spread all-through India on the eve of Eurpean contact.

Finally then, how is Sri Aurobindo’s thought relevant to today’s India? Sri Aurobindo would certainly be unhappy with the parochial and territorial nationalism we have slid into, in the past few decades. To him and others of the spiritual-nationalist thought, India is foremost a vehicle of Dharma, that sympathises with all oppressed people across the world, and seek to bring succour to them. Indeed immediately following 1947, the early Indian leadership was aware of this wider goal of Indian nationalism, when Pandit Nehru stood shoulder-to-shoulder with the leaders of Africa and Asia.

It was this impulse that led her open her arms to the Tibetan freedom fighters, and again later to the oppressed masses in East Pakistan and Northern Sri Lanka. India of those days sought her place as the guarantor of the fights of the minorities in Pakistan. Today, however our vacuous nationalism driven by self-interest does not bother to even offer a few words of solace to those suffering under oppression, whether of Kurds and Yazidis in Iraq under the Islamic State, or Kurds under Turkey, or Sindhis and Balochs in Pakistan. Lost in a hyper-myopic self-interest, India has all-but-forgotten Tibet, and the fate of minorities in Pakistan, Bangladesh and even Kashmir.

The inner spiritual development whereby the individual seeks harmony with the whole of the cosmos, establishing a loving kinship with all life, as proposed by Yoga and its practice in dharma, are the only solutions to the ever-increasing all-round insenstivity to the suffering of the environment, animals, and vulnerable children, women and men all across India, as we march on to the tune of unhindered ‘development’.

The innate sense of harmony and balance that Dharma nurtures, led our ancients to rest the body through fasts, rest the cattle and earth through festivals and indeed balance all expansion through periods of contraction, rest and revitalization. Today, as our ecology totters and our humanity suffers at the face of unhindered greed, the inner poise of Yoga and transformation of human nature by the higher consciousness, which underlies Sri Aurobindo’s thought is all the more relevant. Such an estimation does not require any elaborate scholarship, but rather a sincere inquiry into our own civilizational ethos.

Prabhu Iyer