(Speech given at the Dharma Civilization Foundation’s Strategic Retreat, SVYASA, Jigani/Bengaluru, 5-7 February 2015)

A knife is sharpened by shaving away all the superfluous material that makes it dull. A sharp knife is a live case of “less is more”: less material means more sharpness. At an action-oriented “strategic retreat”, our knife should be sharpened by cutting out ineffective pursuits and misdirected energies. Case in point: the exaggerated use of “decolonization” discourse.

1 . Positive reasons for “decolonization

” Hindus talk a lot about “decolonization”. Me too, I have done it, because obviously it is a process that is beneficial and that has yet to be completed. The good thing about it is the awareness that there is something to get away from. Consumerism, materialism, the foreign language used as India’s hegemonic medium, and the misconstruction of Hindu society founding the politics of casteism, are legacies of British colonialism and of neo-colonialism in the guise of globalization.

Anti-Hindu “secularism” and the psychology of fear, making this an underground society expert at avoiding the thorny issues, are to a large extent a persistent heritage from the preceding colonization by Islam. Even without these specifics, even if the colonizers had perchance only brought good things, I would still be against the subjection of one culture by another, on principle. Let there be no doubt about it: I am all for “decolonization”.

But then, while using the motto “decolonization”, many Hindus make a number of mistakes. In the aggregate, they are now so numerous that the very use of the word sends alarm bells ringing. Indeed, at this very gathering I have heard a speaker on Hindu science who sounded serious enough, but who got badly lost once he ventured outside his field to “decolonize” and pontificate on history. Fortunately it was the only false note thus far, but in Hindu society at large it is alas all too common to justify bad but India-flattering history under the guise of “decolonization”.

2. Defective knowledge of the West

The effect of this discourse of “decolonization” is mostly negative. The least of the obstacles, and the most excusable, is most Hindus’ defective knowledge of Western civilization. As Prof. Balagangadhara Rao has said, Indians tend to think they understand the West just because they are good at making money in the West.

The effect of this discourse of “decolonization” is mostly negative. The least of the obstacles, and the most excusable, is most Hindus’ defective knowledge of Western civilization. As Prof. Balagangadhara Rao has said, Indians tend to think they understand the West just because they are good at making money in the West.

Thus, it is said, even by worthies like Swami Vivekananda, Mahatma Gandhi (though both were familiar with Western spiritualist circles) and Deendayal Upadhyaya (though he may have borrowed his founding term “integral humanism” from French Christian-Democratic thinker Jacques Maritain), that “the East is spiritual and the West is materialist”. One has to be really very ignorant of the history of Western thought to say this. Both pre-Christian, Christian and post-Christian Westerners had or have chosen the life of the spirit, priests and monks as well as men of action.

Indians have perhaps never heard of Marcus Aurelius, Roman emperor, Stoic philosopher and writer of an aphorism collection called Meditations; but many others like him could be cited, and an educated modern Hindu could be expected to know at least some of them. Conversely, Indians have been just as keen on material welfare as the West, from Chanakya’s Arthashastra, the classic on statecraft and economics, down to the proverbial business acumen of India’s banias (entrepreneurial caste).

It would take us too far to go into that large minefield, the Hindu understanding of the Christian factor. Hindus tend to confuse “the West” with “Christianity”, two entities which indeed do overlap, but which should nonetheless be distinguished. The West existed before Christianity, and through Alexander and the Indo-Greeks, the Hindus have had a direct taste of it, as well as a direct cultural influx, e.g. the Buddha statue and Hellenistic astrology. And Christianity existed outside the West, which is no longer its main demographic centre of gravity nor the main recruiting-ground for missionaries to India.

One example, though. More than once I have read Hindu tracts about something called “Christian economics”. By that, apparently they mean capitalism (as opposed to a gentler, more holistic Hindu alternative), which Max Weber famously linked with the Protestant ethos. A key element in capitalist economics is interest, or pejoratively: usury. When the medieval Scholastics prohibited “usury”, they were just as much practising Christian economics as the Calvinists who pioneered capitalism.

In fact, economic liberalism or “capitalism” has always been anti-tradition and anti-hierarchical (reason why Karl Marx partly praised it), and conversely, the Catholic Church was always against capitalism. The social teachings of the Church (encyclical Rerum Novarum, 1892) were a renewal in updated form of the privileges of the craftsmen’s guilds, such as price controls, abolished as obscurantist curbs on freedom by the liberal French Revolutionaries.

The decade of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, when capitalism made common cause with the Catholic Church under the Polish Pope John-Paul II against Soviet Communism, should not deceive us: this was only a temporary and unnatural alliance. When the present Pope, Francis, makes his usual Left-populist noises against capitalism, he is not being a dedicated follower of intellectual fashions (as his pro-free-market critics allege) but a faithful representative of Church tradition.

Similarly, the Biblical injunction for man to subdue the other species does not mean a simple opposition to Hindu respect for other species, or so the Church apologists assure us with an eye on contemporary ecologist trends. It is curtailed by what Christians call “stewardship”: we are not the owners of nature (as capitalism assumes), we are its stewards, the gardeners in God’s creation, and are obliged to look well after the other species.

Christianity is to an extent against freedom, i.e. against the unlimited right to do anything, just as Dharma is. This necessarily makes both of them critical of an entirely arbitrary or “free” conduct, in economics as in other areas. Compare it with how in some countries everybody is required to observe the local building style when designing new houses: the common custom prevails over the individual’s right to just do anything.

So, this brief excursus just to give you an idea of how “Christian economics” is rather more complex than many Hindus assume. Of course, Hindus are under no obligation to know about Christian principles and attitudes, but if at all you want to speak out on them, you’d better first inform yourselves.

3. Defective knowledge of Western influence

Numerous Indian intellectuals (as distinct from thinkers) have taken to citing Edward Said’s book Orientalism (1978) as their gospel on the relation with the West as well as with the classical study of their own culture. The book has been refuted in detail in several counter-books, one of them by the noted South-Asian-born ex-Muslim Ibn Warraq, diagnosing both its numerous factual errors and its over-all conspiratorial framework.

Numerous Indian intellectuals (as distinct from thinkers) have taken to citing Edward Said’s book Orientalism (1978) as their gospel on the relation with the West as well as with the classical study of their own culture. The book has been refuted in detail in several counter-books, one of them by the noted South-Asian-born ex-Muslim Ibn Warraq, diagnosing both its numerous factual errors and its over-all conspiratorial framework.

It effectively reduces all scholars of Asia to agents of the colonial, neo-colonial or American-imperialist entreprise. Catering to the self-hate (“oikophobia”) of Western intellectuals, the polemical interests of the Muslim world and the cluelessness of starry-eyed Hindu wannabes, the book was nonetheless very influential. It became the founding myth of a discipline called “Postcolonial Studies”.

For Muslims, the book was very welcome because it served their position in the debate with the Western scholars who had brought the true religion down to earth. Indeed, in other publications too, Said proved himself a loyal spokesman of Islam. In his book Covering Islam, he pioneered the thoroughly false claim that the media are anti-Islamic. (To the contrary, the media always try to put a positive spin on news stories that by themselves show Islam in a bad light. They only help to tarnish the image of the religion, in spite of themselves, by having to bring some raw news data that cannot but create a negative impression.) So, for Hindus it is not quite rational to parrot this great propagandist of Islam.

Moreover, Hindus (and strictly speaking even Indian Muslims) have a specific reason not to go along with Said’s attempt to demonize the fine name of an academic discipline. In Indian history, the name has acquired a different specific meaning, moreover one that contradicts Said’s conspiracy theory: “Orientalists” was the name of a party within the British ruling class favourable to the use of native languages rather than English as medium of administration and instruction. Some were scholars of Sanskrit, Persian or the vernaculars, other were amateurs, but all had come to identify to a certain extent with native culture. In his (ultimately victorious) plea for the use of English, Thomas Babington Macaulay did indeed call his opponents “Orientalists”.

Even before or without Said’s influence, Hindus have made some mistakes in assessing Western culture. Thus, they seem to be unfamiliar with the factor of change in Western culture. Thus, the human rights discourse presently used by neo-colonial Western-based NGOs (and its Indian allies) in order to pit sections of Indians against one another and particularly to inculpate the Hindu movement, was once used in an anticolonial sense, e.g. against the British massacre at Jallianwala Bagh.

For another example, the present-day association of the West with loose morals dates to the last half century and has nothing to do with the Victorian England whence the colonial Orientalists originated. Indeed, when it came up, old-school Westerners themselves saw their culture fade away in a decadence of Pacific-type nudism (with Margaret Mead’s influential myth of unproblematic sex in Samoa) and rock’n’roll of African-American provenance. The fundamental change from the Christian and racial assumptions of some early Orientalists versus the religious scepticism and progressivism of the contemporary scholars tends to get papered over.

I frequently come across outdated allegations against “white Christian nations”, meaning the West. Even after Colin Powell, Condoleezza Rice and Barack Obama came to power, and even after the majority of missionaries shifted to non-white, this increasingly anachronistic rhetoric continues in some circles.

I frequently come across outdated allegations against “white Christian nations”, meaning the West. Even after Colin Powell, Condoleezza Rice and Barack Obama came to power, and even after the majority of missionaries shifted to non-white, this increasingly anachronistic rhetoric continues in some circles.

In their ivory towers of holy indignation against colonialists like TB Macaulay, Hindu polemicists seem not to have noticed that anti-racism has become the state religion in most Western countries (like anti-communalism, meaning anti-Hinduism, in India). And it is precisely in the name of anti-racism that Hinduism is now being attacked, on the plea that the intrinsically Hindu caste system is based on race.

Likewise, caste is constructed as a form of slavery (a notion eagerly nurtured by many Dalit activists), and precisely because the West has to exorcize its own bad conscience from the past in this regard, it is all the more eager to fight traces of slavery and other injustices in Hindu society. The West is also becoming less Christian, a development that even affects America though more slowly.

But that doesn’t mean that Christian subversion is becoming less. The Churches, who don’t have a nationality, have their own agenda. They are not anyone’s puppets or stooges, neither of the colonial powers of yore nor of the CIA today, as too many Hindus think.

The obsession with old and newer forms of colonialism works on Hindus like a conjuror’s trick: it misdirects their attention. It makes them blind to the realities and challenges of today.

4. Defective realization of one’s own “colonizedness”

The secularists have a whole lot of fun pointing at the RSS uniforms with the brown knickers as typically colonial. These are indeed not representative for the colourful array of Indian styles of clothing. Nor is the central Hindutva dogma of Nationalism: the concept of the nation-state is a typical product of modern Western thought in a particular, now bygone phase.

The secularists have a whole lot of fun pointing at the RSS uniforms with the brown knickers as typically colonial. These are indeed not representative for the colourful array of Indian styles of clothing. Nor is the central Hindutva dogma of Nationalism: the concept of the nation-state is a typical product of modern Western thought in a particular, now bygone phase.

A major influence on the budding RSS was the Arya Samaj. Somewhat like the Brahmo Samaj earlier, it called “true” Hinduism monotheistic. Nowadays, very many Hindus will tell you that in essence, Hinduism is a monotheism. These Hindus are not even aware of the proper meaning of this word. Monotheism does not mean that you worship one God (already requiring a serious reinterpretation of the many Gods effectively worshipped by most Hindus, from the Vedic rishis on down), the way some Hindus choose one God to worship from among many, a phenomenon that scholars of religion call henotheism.

Nor is it the inclusive oneness of a divine essence underlying all the gods, or monism, as enunciated in the profoundest Vedic verses. It means an exclusive worship of a jealous God banishing all others. Mono- does not mean “one”, as Hindus seem to think; it means “alone”, hence “not tolerating another”. It does not say: “Allah and Shiva are one”, it says: “Only Allah is true, burn Shiva.” So far, there is no such jealous God in Dharma.

At any rate, the Hindu appropriation of the word monotheism did not stem from dharmic knowledge, only from a desire to be like the colonizer. In this case, real “decolonization” would mean: not caring about the label “monotheist” nor about the numerical interpretation of the sacred.Similarly, the understanding of religions as separate boxes between which conversion is possible, typical for the Christianity of the last colonizer and the Islam of the earlier colonizer, has entered Hindu consciousness: vaguely as a convention among committed Hindus, but in all seriousness among the secularists.

In fact, however, conversion as in Christianity, with the Frankish King Clovis “burning what he had prayed to, and praying to what he had burned” (remark the false Christian projection of iconoclasm onto the Pagans), firmly abjuring one box to enter another, has never existed in Hinduism.

In fact, however, conversion as in Christianity, with the Frankish King Clovis “burning what he had prayed to, and praying to what he had burned” (remark the false Christian projection of iconoclasm onto the Pagans), firmly abjuring one box to enter another, has never existed in Hinduism.

Nor has the division of the Hindu commonwealth of Sampradayas into the separate religions of Jainism, Buddhism, Sikhism and “Hinduism”. This is a typically colonial construct that has struck roots and is now assumed in all the textbooks. It is only with Dr. Bhimrao Ambedkar in 1956 that we get a “conversion from Hinduism to Buddhism”.

For a lighter example, consider the celebration of birthdays. Given the prevalence of astrology and birth horoscopy in India, at least birth data have been noted down for many centuries, even before the first colonization; unlike in some other cultures. But the celebration of birthdays was rare.

I remember Sita Ram Goel taking a very sceptical view of it when he saw younger people celebrating their birthdays. It was not considered humble, it counted as a narcissistic pastime. Better to worship and to give to the poor than to party and spend on yourself. But it was popularized by birthday scenes in American TV serials, somewhat like Saint Valentine’s day which is still a bone of contention.

This scepticism was not typically Hindu or Indian: my old mother, a devout Catholic, has a similar dislike for birthday celebrations. The old Catholic approach was that you sort of celebrated your “name day”, i.e. the calendar day vowed to the Saint after whom you were named (in the very old days, many people didn’t even know their own birthdays). And then you were not supposed to celebrate yourself, a silly pastime incompatible with the (i.e. any) religious worldview, but to celebrate “your” saint. Nevertheless, with democratization, birthdays are no longer confined to exceptional figures like Jesus (by convention, born on 25 December, i.e. Christmas) or Mohammed (whose so-called birthday was actually the day of his death), so most Westerners make them an occasion for celebration – and now, most Hindus too. Even popular Gurus make a show of their birthdays, though their pre-ordination personalities are supposed to have died. It is one of the many forms of sneaking “colonization” that the Hindus willingly participate in.

5. Rejection of good contributions of the West

The rhetoric of decolonization is also often used for a rejection of the good things the West has brought. Thus, Hindus have always been (and this is not a colonial prejudice) poor at history-writing. Let us not compare with the West, but take China. Of each battle or other significant event in China since ca. 800 BC, we know the exact date. In India, by contrast, even the century in which some famous people lived is controversial.

So, Hindus could do with the key to trustworthy history-writing: the historical method, brought to India by the last colonizer. A number of Hindus have made it their own and written fine history, but there are also many Hindu activist who, pretending a bold and defiant stand against “the colonial version of history”, are scornful of it and continue to write a pre-modern, often fantasy-laden type of history.

In the Aryan invasion debate, I keep hearing from Hindus that comparative-historical linguistics, on which the notion of an Indo-European language family is based, is a “pseudo-science”. In fact, linguistics as such is neutral vis-à-vis the Homeland question, and could be made to support the Out-of-India Theory. Hindus sceptical of the Aryan invasion could have won the Homeland debate fifteen years ago, but they spurned the “colonial” contribution of linguistics and preferred defeat instead.

Fighters consider what can give them victory, not what the origins of a new weapon are. The modern world is witness to a lot of new developments, many of them useful though not always of Indian provenance. Hindus have to make up their minds whether they want victory by using these modern techniques, or “decolonize” themselves into oblivion.

6. Escaping responsibility

African dictators who have ruined their countries and see no escape anymore, always try to justify themselves by invoking the “legacy of colonialism”. This has made us Westerners rather sceptical of the “decolonization” rhetoric. By now, we have become too polite to say it out loud, but when we hear such a “decolonizer”, we yawn and look at each other with a tell-tale expression on our faces: “Oh no, not again.”

African dictators who have ruined their countries and see no escape anymore, always try to justify themselves by invoking the “legacy of colonialism”. This has made us Westerners rather sceptical of the “decolonization” rhetoric. By now, we have become too polite to say it out loud, but when we hear such a “decolonizer”, we yawn and look at each other with a tell-tale expression on our faces: “Oh no, not again.”

“Decolonizing” is a tried and tested way of escaping one’s own responsibility. Thus, Nehruvian socialism was freely borrowed into the young Indian Republic from British Fabian socialism, but it was not forced on anyone by the colonizer, who had just left. It is understandable that Indians were influenced by whatever sources of inspiration were available, but in this case they had a non-British and anti-colonial alternative: Gandhian economics. Whatever its merits, it was a really existing alternative that enjoyed credibility at the time, but which a decisive number of Indians spurned to bring in socialism.

In language, the first choice made by the Constituent Assembly was anti-colonial, viz. for a replacement of the colonizer’s language with a native alternative. Yet, by the due date of 26 January 1965, it was decided to overrule the Constitution and perpetuate English as lingua franca. This was a choice made by Indians, not foisted on them by British colonialism nor by other outside factors like American imperialism. This choice reduced the vast majority of Indians to second-class status.

More recently, we had the change to Western consumerism patterns and Western clothes, the effective adoption of Valentine’s Day, the increasing use of the Gregorian calendar, etc. Whatever their merits or otherwise, all this was done by Indians without any outside pressure. It may well take a colonized mind-set to introduce these Western-originated items, but it was nonetheless done by Indians independent from their former colonizers.

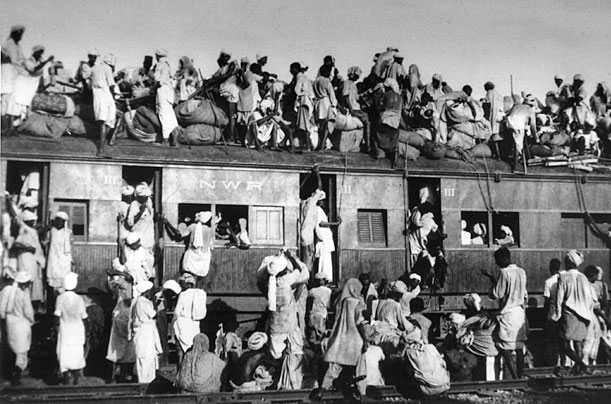

In history, esp. regarding the Partition, we see this self-exculpating rhetoric being used massively: this event with millions of victims is routinely blamed on the British. In fact, it was a wholly South-Asian affair, with the actual guilt being wholly on the side of the Indian Muslims, and with the clumsy and confused handling of this Muslim project by Jawaharlal Nehru and especially by Mahatma Gandhi (who opposed an orderly exchange of population that could have saved a million lives) making the outcome far worse than necessary.

In history, esp. regarding the Partition, we see this self-exculpating rhetoric being used massively: this event with millions of victims is routinely blamed on the British. In fact, it was a wholly South-Asian affair, with the actual guilt being wholly on the side of the Indian Muslims, and with the clumsy and confused handling of this Muslim project by Jawaharlal Nehru and especially by Mahatma Gandhi (who opposed an orderly exchange of population that could have saved a million lives) making the outcome far worse than necessary.

The British had roundly opposed the partition of their Jewel in the Crown, until Lord Louis Mountbatten as the last Viceroy accepted the inevitable during the spring of 1947. This was 7 years after the Muslim League’s Pakistan Resolution and after BR Ambedkar’s sarcastic immediate acceptance of it, and months after prominent Congressmen had accepted it as inescapable and as the lesser evil.

But this false history is secretly welcomed as having the merit of avoiding a bitter truth about Islam. The British are safely gone and it is easy to take a heroic-looking stance against them. By contrast, saying the truth about Islam takes courage. So you avoid that but put a brave face on your escapism by calling it “anti-colonial”.

7. Hyperfocus on the colonial period

Deeply ingrained in contemporary Hindu activism is a hyperfocus on colonial-age personalities. Thus, Swami Vivekananda is over-glorified and made the patron of too many institutions. He was admittedly crucial in instilling self-confidence in the Hindu population smarting under colonial rule, but that doesn’t justify his flaws. Thus, scholars of Hindu philosophy consider his knowledge of the same very third-rate, and his influential interpretation of Patañjali’s Yoga Sutra even harmful.

Deeply ingrained in contemporary Hindu activism is a hyperfocus on colonial-age personalities. Thus, Swami Vivekananda is over-glorified and made the patron of too many institutions. He was admittedly crucial in instilling self-confidence in the Hindu population smarting under colonial rule, but that doesn’t justify his flaws. Thus, scholars of Hindu philosophy consider his knowledge of the same very third-rate, and his influential interpretation of Patañjali’s Yoga Sutra even harmful.

The Ramakrishna Mission which he founded, interiorized Christian assumptions (such as that monks should do charity work) and betrayed its founder’s pride in Hinduism by trying to deny its own Hindu identity. But secularists look with satisfaction on Hindus’ veneration of him as they highlight his “Muslim body, Vedanta brain” statement which legitimizes Islam.

So, there are several sides to Vivekananda, and after more than a century, he deserves a more nuanced assessment. Another hero of the Hindu movement is Shivaji, who rebelled against an earlier colonizer. There is little wrong with his brave and shrewd struggle against the Moghul oppressor, the wrong thing about venerating him is that it blinds Hindus to all the earlier builders of Hinduism. If you ask a Hindu on the street who Dirghatamas was, you are not likely to get an answer. He was not a decolonizer, a fighter against colonial oppression, but a mere Vedic seer. He only built the civilization that Shivaji and Vivekananda tried to liberate and revive.

Many Hindu pleas against the Aryan Invasion Theory are not about the Aryan question at all, but about the real or imagined machinations by colonial-age scholars like Friedrich Max Müller. Instead of looking back to the glorious age when their ancestors made history by spreading the Indo-European language family, some 5000+ years ago, these Hindus are fixated on how the colonial-age scholars looked at that history. It is like sitting in a room and being asked to describe a tree in the distance: you look at the tree through the window, then start describing the window rather than the tree. But I don’t want to know about the window, I want to know about that tree. And the Aryan debate is not about what happened 150 years ago, it is about what happened 5000 years ago. Loud claims of decolonization only hide a fixation on the colonial period.

It is necessary for Hindus to look farther back. The history of Hinduism fighting for its survival must of course be written, but at the centre of Hindu historical consciousness should be the more creative period, when Hindus spent less time on defending their civilization and more on developing it.

8. Conclusion

For all the reasons enumerated above, I propose a moratorium on the words “colonial” and “decolonization” for the coming years, just to kick the habit.

Well, no, let me amend that. The proposal would make a fine newspaper headline, but I am past the age of seeing the world in black and white. So, it should sound more like this: when at all you are going to use the term “decolonization”, think twice whether it is really appropriate and whether it genuinely conveys the concern you mean to articulate.

9. Postscript: “swaraj in ideas”

In a comment on my lecture about the notion of “decolonization”, someone proposed to use a different term, viz. “swaraj in ideas” (swaraj = “self-rule”, independence”). The same term, apparently launched by philosopher KC Bhattacharya, had in fact been used a few days earlier by a secularist intellectual, Akeel Bilgrami, in an interview given to Rajgopal Saikumar: “‘Hindu Right’s appropriation of svaraj is hypocrisy’” The Hindu,3 February 2015. Bilgrami had given a lecture “reinterpreting Mahatma Gandhi’s notion of swaraj as being not only independent of the West but also a critique of it”.

The professor at New York’s Columbia University and author of Secularism, Identity and Enchantment (2014) was asked to explain what autonomy and intellectual self-determination could mean to India in the current political context. Though a self-declared enemy, to Hindu activists he should be worth listening to and learning from.

Thus, he was asked whether recent events such as rewriting of history books or valorizing ancient Indian technology count as an exercise in “swaraj in ideas”. So: “The issues here are so elementary that in a sane society they should not even be discussed. Much history is a matter of interpretation; there are clear criteria for what counts as evidence for certain conclusions.

The rewrites and valorisation are myth-making, not subtle controversies over how to interpret historical fact. There is nothing subtle at stake in what is being done by the present government and its mandarins in the academy. They are myth-makers passing off as historians. But I am not saying that myths are not an essential part of culture, even modern culture. It is their conflation with historical issues, issues that should be assessed on grounds of evidence that I am saying is an elementary fallacy — so elementary that it should go without saying that it is laughably fallacious. And this is not just a new phase of distortion of ideas and historical method. It was very much at stake in the discussions around Ayodhya.”

The last sentence is an artful attempt at suggesting that the Leftist historians were right after all with their negationist position on the history of temple destructions, quod non. But it is true that in the wider context of the Ayodhya debate, some mixing of myth with history has come into focus, such as belief that the Ram Setu rock formation between India and Lanka was a man-made bridge. I am sorry if I offend any people here, but it is clear to me that this story-line is the typical result of the conventions of story-telling. Even if a story-teller is relating real historical events, such as perhaps the abduction of Sita by Ravana and her liberation by Rama, he tends to weave into his story any elements that are present and could be made meaningful. Thus, a rock-formation right in the place where the story requires the heroes to have crossed the water suggests the remnants of a bridge, and this would embellish the story. It is not profounder than that, there is no need to take this story-line literally.

A crucial challenge to a Hindu government is not to throw away the “Western” contribution of historical method and critical sense in the name of “decolonization”, and not to identify Hinduism with superstition or plain silliness. Note the enemy’s fierce determination in attacking the government’s performance regarding history-writing to take a measure of the challenges before it. For decades, the Hindu movement has cultivated a lackadaisical attitude towards scholarship, thinking that it could buy scholars in the marketplace when a need arose, a gamble that narrowly succeeded in the Ayodhya debate. For the very serious task of organizing an overhaul of the history textbooks, it will, after several failed attempts, have to weed out or at least render inconsequential the very strong tamasic (“dark”, superstitious) tendencies among eager Hindu history-rewriters.

This somehow brings Bilgrami to an attack on reconversion: “Incidentally, one of the current myths can be detected in the notion of ‘ghar vapsi.’ Even those who have criticised the menacing and manipulative aspects of these conversions have not made the deeper point that even if there is no coercion in the conversions, the idea of a ‘ghar’ [home] here is wholly mythical. The Hindu nationalist idea of Hinduism has never been of a ghar for everyone. It has been a ghar only for the brahmanical strata. Of course, India was home to diverse peoples, but that is not the India that has appeal for Hindu nationalists. Their Hinduism has never been conceived as a ghar, so there cannot be a ghar for anyone to return to.”

This conflation of Hindu traditionalism including the caste system with Hindu reformism (represented in its Nationalist form by the Hindutva movement) contains the usual anti-Brahminism. Bilgrami’s arbitrary allegations of “manipulative and menacing aspects” of reconversion stand in contrast with the secularist silence on or even defence of the long-standing conversions to Christianity, well-documented to have those same aspects in reality. Also note that anti-Brahminism, a classic case of a bad and partisan version of history as well as the Indian counterpart of anti-Semitism, can earn you a professorship in New York.

Bur the main reason for going into the Bilgrami interview here, is this comment: “As for the Hindu Right’s appropriation of svaraj — it is sheer hypocrisy. On all these matters of fundamental importance (such as implementing the ideas of ‘development’ formulated by falsified economic theories perpetrated in the West), the present government and indeed the present intellectual ethos among the middle classes, far from being svarajist, is slavishly following countries such as the U.S.”

Real decolonization would be useful on the economic and pop-cultural front, where Americanization is now all the rage. It is, sorry to say, massively facilitated by the Modi (as earlier by the Vajpayee) government. “Down with Nehruism” to them means ”here with Americanism”.

Real decolonization would be useful on the economic and pop-cultural front, where Americanization is now all the rage. It is, sorry to say, massively facilitated by the Modi (as earlier by the Vajpayee) government. “Down with Nehruism” to them means ”here with Americanism”.

Already in 2005, Shrikant Talageri observed that Leftists and Congressites had protected native arts and handicrafts, not as a matter of “Hindu greatness” but because it was “folk art”, “tribal art” or “pre-colonial art”, or just to make a defiant anti-Western gesture. By contrast, the BJP government cared so little about Hindu artistic traditions that it had thrown these collections to the wolves of the market forces, having by then become economic liberals. It turned out that in the name of Hindu revival, you could organize a more effective attack on Hindu traditions than in the name of Karl Marx.

Yes, Nehruvian socialism needed a corrective. The enormously stifling effect it had on Hindu enterprise and creativity needed to be remedied. But Hindu civilization is richer and more resourceful than to need the opposite extreme of Americanization. The Sangh Parivar, once in power, proved itself too unimaginative to think up true Hindu solutions, true “swaraj in ideas”.